Autocrats such as Vladimir Putin use elections strategically as a signalling game to demonstrate their capability to secure the necessary votes. This primarily benefits the regime’s inner circle and rent-seeking elites who rely on Putin’s presidency for their wealth.

Although a notable proportion of the Russian population regards the election and Putin’s leadership as legitimate, their support for Russia’s military actions in Ukraine is waning. Only a slim majority backs the continuation of the conflict.

Despite the oppressive political environment, opposition initiatives such as “Noon against Putin” manifest ongoing resistance. These actions were reflected in vote tallies abroad, where support for Putin was dramatically lower than in Russia.

The post-election period is likely to see the persistence of Russia’s current domestic and foreign policies, with the potential for increased societal and economic tensions. The declining support for the war could further complicate the regime’s efforts to maintain a unified front. This could potentially impact Russia’s global standing and internal stability.

Introduction

After Russia held its presidential election on 15–17 March this year, President Vladimir Putin was declared the winner with 87% of the vote amid a turnout exceeding 77%. This revealed an unprecedented level of oppression, censorship, and outright fraud. Of the thirteen candidates who publicly announced their intention to run, only four made it onto the ballot. As in previous elections, no real competition was expected: No officially nominated rivals dared to promote themselves, duly endorsing Putin’s candidacy instead. The Russian opposition called for the election not to be recognized as legitimate, and electoral forensics stated that some 22 million votes had been stolen.

Why do the Russian authorities still bother to hold elections when it is obvious that they are a sham? Even the President’s spokesman, Dmitry Peskov, has referred to elections as a rather “costly bureaucracy”. What does the conduct of these elections indicate about the state of the Russian regime and Putin’s political support?

Elections, even in hegemonic authoritarian regimes, serve as a litmus test for the resilience of the political system and the regime's ability to project strength and unity.[1] This Briefing Paper argues that Russia’s 2024 election, both procedurally and politically, can be viewed through the prism of a signalling game – an ultimate test of the robustness of the political system. Given Putin’s role as the focal point for the Russian elites[2] and as the guarantor of their economic and political assets,[3] these elites are keen to test his ability to secure a technical electoral victory. Another goal was to demotivate and dishearten opposition-minded voters. From this perspective, international legitimacy as well as electoral integrity were of secondary importance – it does not matter how dirty the game was, what really matters is that the game was won.

This paper focuses on three primary aspects of the election: the Russian regime’s strategies to suppress the remnants of the opposition and control the electoral process; the links between Putin’s popularity, the war in Ukraine, and electoral success; and the development of more nuanced forms of resistance in the constrained political landscape. The paper draws on the “Panel Study of Russian Public Opinion and Attitudes” (PROPA), an online survey of Russian citizens conducted by the University of Helsinki in cooperation with the author of the Briefing Paper. The survey was carried out from 13 to 21 March and garnered a total of 4,757 complete responses. The sample parameters are closely aligned with the population data in terms of demography.[4]

The regime’s strategy: Staging risk-free elections

The path to the ballot box in Russia's presidential election was tightly controlled and manipulated to ensure that no real threats to Putin's rule could emerge. There were only two openly anti-war candidates who attempted to campaign: Yekaterina Duntsova, a member of a municipal assembly and journalist from Rzhev in the Tver Oblast, and Boris Nadezhdin, a liberal but systemic politician from the Civic Initiative party. The disqualification of independent candidates like Duntsova and Nadezhdin underlines the regime's pre-emptive measures to suppress any potential opposition voices that could galvanize public dissent.

This strategy of suppression also encompasses a broader spectrum of tactics aimed at stifling opposition, such as extending the number of voting days from one to three, introducing online voting, and the strategic use of state-controlled media. These measures not only dilute the effectiveness of election observers, but also curtail any meaningful participation by the opposition, ensuring a controlled and predictable electoral outcome.

In the run-up to the election, there was a clear state of excessive bureaucratic tension, as delivering votes for Putin became a task for the entire bureaucratic chain of command, including the presidential administration, governors, municipalities, and election commissions. Putin's strategy was decidedly risk-averse, preventing any candidate who could potentially facilitate coordination against him. This approach led to repression and crackdowns on the remnants of domestic opposition, culminating in the physical elimination of Putin’s main opponent Alexei Navalny, while he was serving his decades-long prison sentence. Massive opposition rallies were neither expected nor feasible. The government's determination to maintain order and a controlled environment was further underscored by the deployment of riot police and pre-emptive measures against potential unrest.

Extending the voting period from one to three days and introducing online voting in 30 regions were key moves designed to facilitate controlled participation. This approach was particularly aimed at urban centres and annexed territories, ensuring a broad yet manageable voter turnout. At the same time, the measures made the work of election observers and the collection of evidence of fraud more complicated.

Early voting, which started on 26 February and lasted until 14 March, enabled residents in remote areas of 37 Russian regions and territories annexed from Ukraine in 2022 to cast their ballots. With over three million online voting applications submitted, it became clear that this digital approach not only served to engage more voters, but also to skew the results in Putin’s favour. It proved particularly effective in urban areas, known for their modern lifestyles and higher potential for protest votes.

This presidential election was marked by a historically high turnout of 77%. This is not uncommon in personalist dictatorships and often represents mobilized votes. In Russia, employers, especially large industrial and public sector companies, operate as brokers in getting voters to the polling stations.[5]

According to the PROPA survey, more than 71% of respondents planned to vote, 5% stated that they had already voted, and only 15% said that they would abstain. However, these figures may have been inflated by respondents with opposition views who showed up to spoil their ballot, or to vote for any candidate but Putin. The anomalous turnout is thus a mixture of mobilized pro-regime voters and, to some extent, non-systemic opposition voters.

This was the dirtiest election in Russia’s post-communist history. The independent domestic election watchdog organization Golos, whose leader Grigorii Melkonyants is currently in jail, described the election as an imitation of democratic processes, marred by extensive vote tampering, restrictions on election observers, and voter pressure. Ultimately, the Kremlin did everything it could to reduce public oversight opportunities and the gathering of evidence of fraud.[6]

Do Russians regard the elections as legitimate?

Despite the abundance of evidence confirming the pervasiveness of fraud and other forms of electoral malpractice, Russian voters by and large still view these elections as legitimate. According to the PROPA survey, approximately 26% of respondents questioned the procedural legitimacy of elections, while 60% deemed them legitimate. These numbers largely coincide with the levels of political support for Putin as president. According to the survey, 74% of respondents supported Putin; those in favour of the current regime are also more likely to see elections as procedurally legitimate.

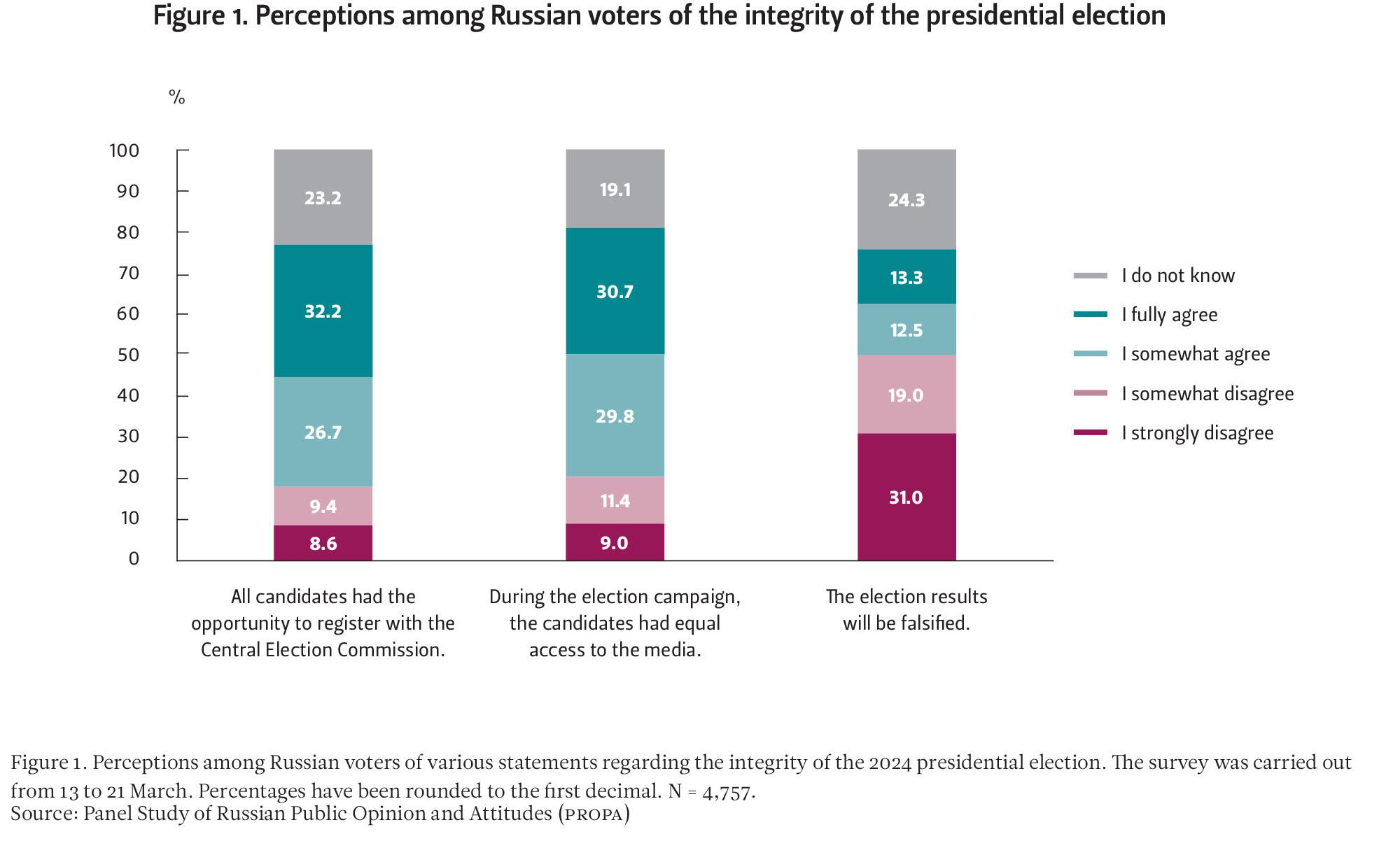

The majority of respondents believed that all candidates had equal access to the media (60%), had an opportunity to register as a candidate (59%), and that there was no fraud (50%) (see Figure 1). Remarkably, almost a quarter of the respondents did not answer the question concerning fraud, 19% were unable to judge whether the presidential candidates had equal access to the media during the electoral campaign, and 23% replied “Do not know” to the question about equal access to the registration procedure. These figures are high and may indicate that these questions were considered sensitive and therefore respondents preferred not to answer.

Acceptance of questionable electoral practices might reflect a broader normalization of such measures within the political culture of the Russian state. In authoritarian regimes, where the dissemination of information is tightly controlled and dissent often suppressed, public perceptions of what constitutes a legitimate election can be significantly altered. This normalization stems from a combination of state propaganda, the absence of strong opposition voices, and a reluctant acceptance of the status quo among citizens.

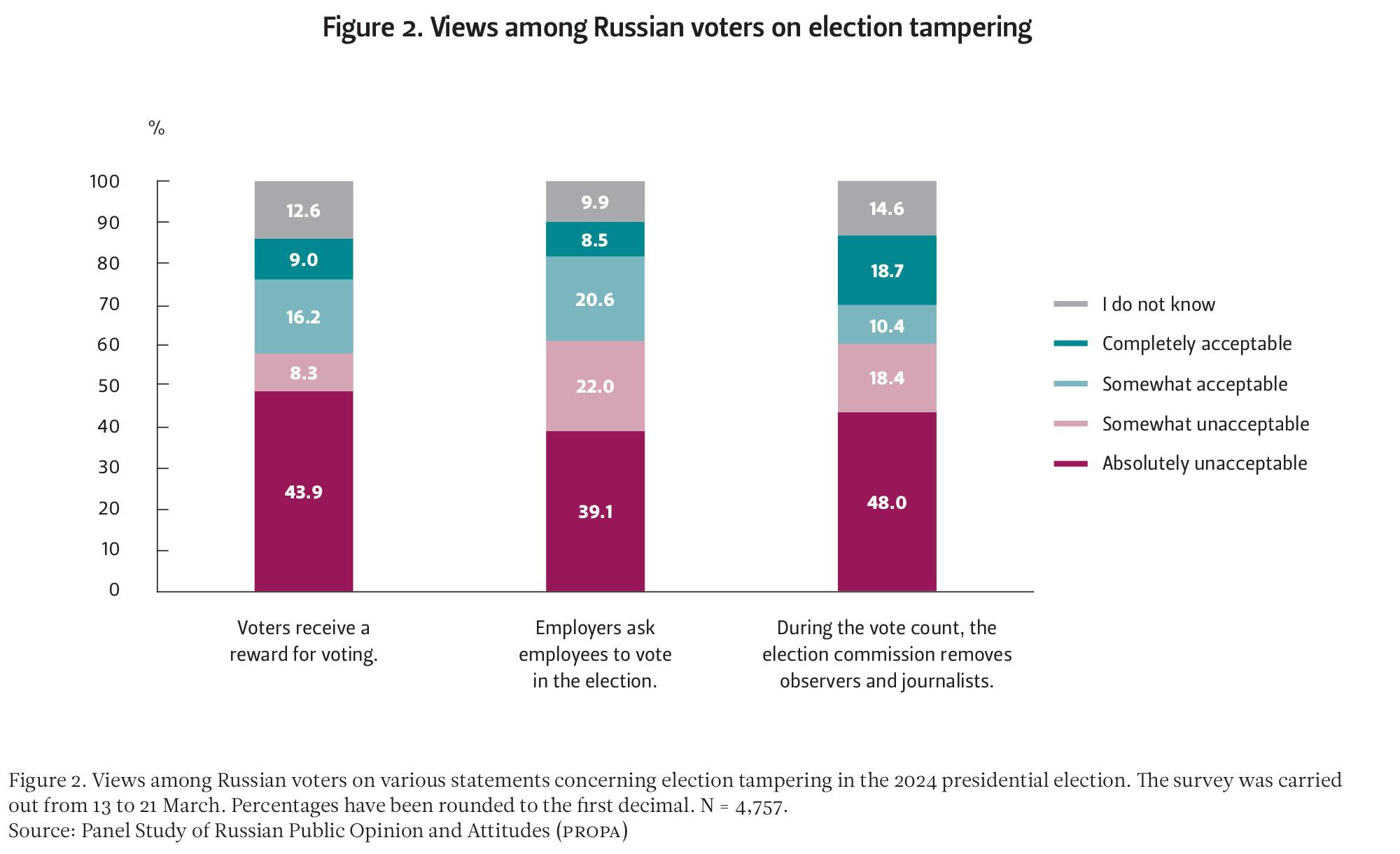

Approximately 66% of respondents felt that removing or restricting the access of election observers was unacceptable. Attitudes towards vote buying were similar – 62% deemed it unacceptable. Based on the answers to these two questions, Russian respondents tend to agree with international principles of free and fair elections. Workplace mobilization – when an employer demands employees to go to the polls and sometimes even controls how they vote – was acceptable as far as 29% of respondents were concerned. While 60% deemed it unacceptable, this nevertheless suggests that certain practices of authoritarian regimes are considered acceptable by some groups of voters.

The Russian authorities implemented extensive measures to inhibit election observers from gathering evidence or exposing any instances of fraud to the general public, thereby aiming to forestall a potential backlash. This strategy included restricting observers’ access to polling stations, closely monitoring their activities and, in some cases, outright intimidation. Such actions were likely designed to maintain a veneer of legitimacy around the electoral process, while ensuring that the actual mechanics of the vote remained obscured from public scrutiny. By limiting independent verification of the electoral process, the authorities sought to pre-empt any questions or doubts that might arise among ordinary Russians about the fairness and integrity of the election. This approach reflects a broader tactic often employed in authoritarian regimes to manage public perceptions, thereby consolidating power without facing significant opposition.

Support for the war declines, support for Putin remains high

Notwithstanding the lack of integrity in the election, a survey conducted by the Levada Center in January reported over 77% support for Putin.[7] However, other independent polls, conducted in early March, reported that only 55% would vote for Putin[8] – which is much less, but still constitutes a majority. According to the PROPA survey, 74% supported Putin as president, 63% claimed that their most preferred candidate was running for president, while 14% claimed that there was no such candidate. A total of 9% of respondents unequivocally stated that their candidate was not on the ballot, and 14% refused to answer the question. Thus, while the majority of respondents claim that they are represented, at least one quarter do not feel this way.

However, this apparent support does not fully translate into support for the ongoing war in Ukraine. Data from the Russian Election Study (RES) reveal that among Putin's supporters, only a slight majority, 54%, endorse continuing the war, with a notable proportion expressing opposition or uncertainty.[9] Even more modest results were found in the PROPA survey conducted in March, which showed that 43% of respondents support the war.

Support for the war is dramatically lower among women than among men: only 38% of women are in favour, compared to 56% of men. Overall support is lower in the regions most impacted by the military draft and with the highest death tolls among males of military age – Buryatia, Altai, and Zabaikalskii krai. There is significant anti-war sentiment among specific demographic groups, notably women and rural residents more affected by military recruitment. Such sentiment, coupled with potential economic challenges, could erode Putin's base.

Growing war fatigue, along with fears of new military drafts, somewhat eroded active support for the war. Meanwhile, the media campaign broadcast across Russia painted a picture of normalcy and positivity. The Russian internet was awash with both overt and covert propaganda, permeating popular shows, and output from influencers and bloggers. Interestingly, the media's portrayal of Putin was carefully curated, seldom linking him directly to the war or explicitly presenting him as a candidate. Instead, his image was crafted around domestic politics and the allocation of state benefits, a strategic move to maintain this perception among the population.

The conspicuous lack of an aggressive campaign for Putin, focusing instead on his presidential duties rather than his candidacy, reflects a strategic dissociation from electoral politics and the ongoing war. This approach helps to preserve his image as a national leader above the fray. Thus, highlighting the costs of the war for Russian citizens is a way to further erode Putin’s support base.

Resistance at the polls in a constrained political landscape

After Navalny’s death, his team organized a protest called “Noon against Putin”. They urged people to vote at noon on the last day of the three-day election as a safe form of dissent, with the aim of showing solidarity and raising the stakes for any election tampering.

Despite the oppressive political environment and the near impossibility of altering the electoral outcome, unorthodox forms of resistance and protest persist within the Russian political landscape. The mass gatherings of voters at polling stations to spoil their ballots, as well as the symbolic protests by Russian dissidents, signify a defiance that transcends the conventional avenues of political engagement. These acts of protest, albeit symbolic, highlight the resilience among segments of the Russian population. They seek to reclaim agency and voice in a context where traditional political mechanisms are rendered ineffective by state repression.

Protesters gathered in long queues chanting slogans outside Russian embassies and consulates around the world, especially in London, Berlin, and countries with large populations of Russian wartime migrants, turning out in droves to demonstrate their solidarity. Although these actions were presented by the official Russian media as “exceptional enthusiasm”, the main message was aimed at the host societies, signalling that Russian nationals abroad have diverse political attitudes and do not necessarily support Putin and his political course. For example, in Finland, Russians voted for Vladislav Davankov (New People party) over Putin. Putin received only 33% of the total vote, while back in 2018 he gained 73%.

The organization of domestic protests has become more dangerous and violent. During voting in several Russian cities, ballot boxes were set on fire, and doused with ink, iodine, and bright green dye. Some voters were detained based on the messages they wrote on their ballot papers, which meant that the principle of secrecy had been violated. Around one hundred people are going to face criminal charges under Article 141 of the Russian Criminal Code, “Interference with the exercise of electoral rights or the work of electoral commissions”.[10] Those involved in these cases face up to five years in prison, with the State Duma raising the issue of extending the sentence to eight years. All of this unequivocally documents a further increase in repression.

Conclusions

The post-election period in Russia is likely to see a continuation of the current domestic and foreign policies. The ongoing war in Ukraine, despite declining support for it, and Russia’s reorientation towards the economies of the Global South and Asia suggest a strategic alignment designed to cope with increasing international isolation and economic pressure. The government might introduce unpopular measures such as new military drafts or economic austerity – although the probability of the latter is relatively low now – which could further tighten the regime's control over citizens’ rights.

Elections in Russia, albeit predictable and controlled, remain a crucial mechanism for the regime to assert its legitimacy and manage internal elite dynamics. They simulate a participatory political process and provide a veneer of democratic activity that helps to stabilize and perpetuate the current power structure. Future elections are expected to function in a similar way, reinforcing the regime’s grip while allowing for minor political adjustments to ensure loyalty and efficiency within the government.

Despite the oppressive political environment, unorthodox forms of resistance, such as protests and acts of defiance at polling stations, demonstrate that segments of the Russian population continue to seek avenues for expression and change. While these acts of resistance are largely symbolic, they underscore a persistent dissatisfaction and the potential for increased civil unrest, particularly among the demographics most affected by the regime's policies.

The diminishing public support for the war in Ukraine poses significant challenges for the regime's ability to maintain the illusion of large-scale support. This growing discontent, which is particularly pronounced among women and those directly affected by the military drafts, could lead to a gradual erosion of support for Putin’s leadership, complicating his administration's efforts to project strength and cohesion domestically.

The long-term effects of these elections and the ongoing policies are likely to influence Russia’s global standing and internal stability. As the government potentially escalates repressive measures to manage discontent and maintain control, Russia may face further international condemnation and internal fragmentation, affecting its position on the world stage and the quality of life of its citizens.

Endnotes

[1] Magaloni, Beatriz. Voting for autocracy: Hegemonic party survival and its demise in Mexico. Vol. 296. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006; Gehlbach, Scott, and Alberto Simpser. “Electoral manipulation as bureaucratic control”. American Journal of Political Science 59.1 (2015): 212–224.

[2] Hale, Henry E. Patronal politics: Eurasian regime dynamics in comparative perspective. Cambridge University Press, 2014.

[3] Yakovlev, Andrei. “Composition of the ruling elite, incentives for productive usage of rents, and prospects for Russia’s limited access order”. Post-Soviet Affairs 37.5 (2021): 417–434.

[4] Zavadskaya M., Vyrskaia M., Gilev A. (2024) Panel Study of Russian Public Opinion and Attitudes (PROPA):

Wave 1. DiscussData (forthcoming).

[5] Frye, Timothy, Ora John Reuter, and David Szakonyi. “Political machines at work: Voter mobilization and electoral subversion in the workplace”. World Politics 66.2 (2014): 195–228.

[6] “Russian Presidential Vote an ‘Imitation’, Election Watchdog Golos Says”. The Moscow Times, 18 March 2024. https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2024/03/18/russian-presidential-vote-an-imitation-election-watchdog-golos-says-a84511.

[7] “Conflict with Ukraine: estimates of the end of 2023 – beginning of 2024”. Levada Center, 27 March 2024. https://www.levada.ru/en/2024/03/27/conflict-with-ukraine-estimates-of-the-end-of-2023-beginning-of-2024/.

[8] A poll conducted before the election: https://www.extremescan.eu/post/7-study-of-russian-residents-electoral-actions-on-15-17-march-2024.

[9]Frye, Timothy et al. “Putin’s hidden weakness. New evidence shows many Russians support him – but not the war”, Foreign Affairs, 25 March 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/russian-federation/putins-hidden-weakness?check_logged_in=1&utm_medium=promo_email&utm_source=lo_flows&utm_campaign=registered_user_welcome&utm_term=email_1&utm_content=20240401; The RES survey was conducted by the independent and reputable Levada Center, although Levada's own reports as of January 2024 still documented relatively stable support for the war cause. Due to Levada’s status as a foreign agent in Russia, and the rules governing the conduct of electoral campaigns, Levada is not in a position to publish opinion polls within two months prior to polling day. Nevertheless, three independent sources have registered a decline in support for the war.

[10] “Chronicle of political persecutions in March 2024: key points”, OVD Info, 12 April 2024. https://ovd.info/2024/03/14/vybory-prezidenta-rossii-zaderzhaniya-i-davlenie.