Turkey’s long-term search for strategic autonomy, shifting global power relations, and Central Asian governments’ desire to foster multi-vector foreign policies have prompted Turkey to successfully intensify its activities in Central Asia.

From the 1990s onwards, Turkey’s activism in Central Asia has strengthened cultural, trade, and diplomatic relations. Its multilateral coordinating body, the Cooperation Council of Turkic Speaking States, is being further institutionalized into the Organization of Turkic States.

Turkey’s potential for acquiring a greater role in the region is limited. Its economic engagement remains modest, and Central Asian states’ responses to the Taliban takeover in Afghanistan indicate that Russia and China remain the region’s preferred security partners.

Although Turkey, China, Russia, and other external actors compete in Central Asia, no full-fledged confrontation has taken place in the region so far. Turkey’s new initiatives are unlikely to change this dynamic, as long as they are conducted in the spirit of inclusive multipolarity.

Introduction

The regional geopolitical balance in Central Asia is undergoing a change. The US withdrawal from Afghanistan and the Taliban’s rise to power, the long-term rise of China, and the gradual but steady decline of Russia which, economic power excluded, is still the most powerful external actor in the region, are developments that are shaping Central Asia’s position in world politics. Furthermore, they are framing individual states’ foreign policy choices, which are inductive to the region’s changing outlook. For example, Uzbekistan’s international opening following the 2016 leadership change has generated new potential for interregional and multilateral collaboration.

In this context, middle powers such as Turkey, Iran, and Israel are also updating their policies for the region. This Briefing Paper focuses on Turkey and asks whether it is rising to prominence in Central Asia. Studying Turkey’s relations with Central Asian states is particularly timely given the “Eurasian shift” in Turkish foreign policy, Turkey’s pivotal role in the second Karabakh war of 2020, and renewed efforts to solidify pan-Turkic initiatives in the region.

The study identifies Turkey’s current interests towards Central Asia and studies their compatibility with the aspirations of the five post-Soviet states of Central Asia, especially the four Turkic republics of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. It explores the shared interests while also noting diverging views and unmet expectations across the border. While the Central Asian states and Turkey have found a common language in trade, cultural exchange and arms trade, they have somewhat contradictory positions on political Islam and state sovereignty.

The Briefing Paper argues that there is sufficient convergence of interests to propel Turkey’s greater presence in Central Asia. However, the scope and speed of Turkey’s rise can remain modest. On the one hand, this is due to Turkey’s limited economic capacity, foreign policy overstretch, and limited expertise on contemporary Central Asia in President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s inner circle. On the other hand, the actors involved are likely to hesitate about committing to fostering the relationship if it faces a resolute pushback from Russia.

Turkey and Central Asia in the 1990s: Enthusiastic but limited collaboration

The idea of a cultural and linguistic bond with Orta Asya Türkleri (Turks of Central Asia) had a long pedigree in the pan-Turkic ideology prevalent in the last decades of the Ottoman Empire. At the time, the notion of a political union and overall modernization of all Turkic peoples was advocated by intellectuals in both the Russian and Ottoman Empires. With the collapse of the Soviet Union and the establishment of independent Turkic republics in 1991, Central Asia became a major direction in Turkish foreign policy.

In the 1990s, Turkish interest towards Central Asia manifested itself in various ways. Turkey was the first country to recognize the five newly independent states in the region. From 1991 to 1993, Turkey and the Central Asian republics signed over 140 agreements in political, cultural, economic, and military affairs. Ankara established the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency (TİKA) to coordinate various aid and development projects targeting Central Asia and South Caucasus. Between 1992 and 1996, 90% of all development aid to Central Asia came from Turkey.[1] These initiatives laid the groundwork for the establishment of the Cooperation Council of Turkic-Speaking States, an umbrella organization for cooperation, in 2009.

The focus on perceived cultural proximity that formed the core of Turkey’s strategy in Central Asia failed, however, to resonate among Central Asian elites and populations, even if Turkey was perceived as an interesting role model for state and societal development. Turkish politicians who enthusiastically talked about a vast Turkic world stretching from the Aegean Sea to China’s Xinjiang were applauded at home, but in Central Asia, Turkey’s big brother mentality clashed with Central Asian leaders’ eagerness to embrace sovereignty after Soviet rule. There were also economic factors that contributed to Turkey’s failure to gain influence in the region. The lack of robust financial and technological power in Turkey and the limited trade infrastructure in Central Asia meant that the level of Turkish trade and investment fell short of Central Asian governments’ expectations, although Ankara’s involvement was indeed considerable in some sectors, such as construction, telecommunications, and textiles.

From the 2000s onwards: Multivectorism and Eurasianism

The ‘multivectorism’ of Turkish foreign policy, encompassing a variety of foreign policy objectives and cooperation partners without giving priority to any, has been gradually strengthened by the Islamic-conservative Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, AKP), in power since 2002. Yet one could argue that Turkey’s international outlook already had a multivectoral character in the mid-1990s, even if integration with the West, particularly with the European Union, still consumed most of its energy. From the 2010s onwards, Turkey’s aim has been to support the multipolarity of the global order and the country’s strategic autonomy. Following this, Ankara has sought to project its power in the Middle East, Africa, and the Eastern Mediterranean, while making many adversaries at the same time.[2] At present, Turkey perceives Central Asia as one of the zones where it could increase its influence.

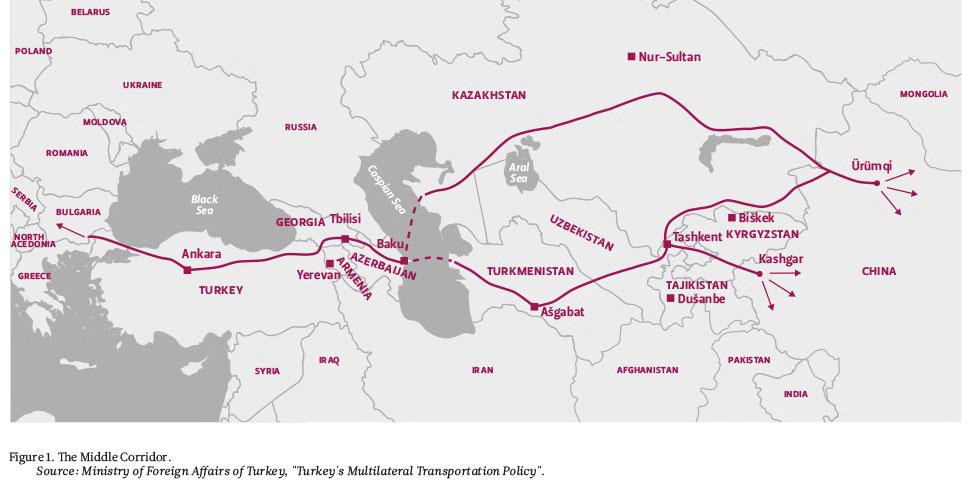

Another factor explaining Turkey’s engagement with the region is China’s expanding global role and its major connectivity projects in Central Asia. While in 2009 President Erdogan famously called Chinese repression of the Uyghurs a “genocide”, in 2019, Turkey abandoned its position as a supporter of China’s Uyghur minority. The AKP government, supported by wider domestic constituencies, seeks to foster good relations with China. This “Eurasian” shift has been demonstrated by Turkey’s attempt to coordinate its own connectivity projects, in particular the so-called Middle Corridor, still underdeveloped, with China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The Middle Corridor, conceptualized by Ankara as an important step towards reviving the ancient Silk Road, passes by rail and road through the South Caucasus and the Caspian Sea, reaching China through Central Asia.

Turkey’s attempts to improve the East-West connectivity in the South Caucasus and Central Asia have received a warm welcome in Beijing. Conversely, Russia has followed Ankara’s Eurasian shift with some concern given its own interests in the region. Although Turkey-Russia relations have been defined by an overall strategic rapprochement, the two countries’ geopolitical aspirations remain partly incompatible and the level of trust among the political elites is low. At present, Moscow seems to accept Turkey’s growing influence in Central Asia as long as it remains limited.

Indicators and avenues of Turkey’s increasing role

By supporting Azerbaijan in the second Karabakh war in autumn 2020, Turkey showcased its military technological advancement and its willingness and ability to remake the regional status quo. Furthermore, the war has raised hopes in Turkey and Azerbaijan for a transport corridor through Armenia that would allow Turkey to bypass Georgia and Iran in accessing the Caspian Sea and eventually Central Asia. The Azerbaijan-Turkmenistan memorandum of understanding on the joint development of the disputed Kepez/Serdar offshore oil and natural gas field, signed in January 2021, combined with plans for new pipelines, is a step in the consolidation of the Azeri-Turkish cooperation that is in Ankara’s interests.[3]

Even if Turkey failed in its attempt to rise to prominence in Central Asia in the 1990s, the lack of success did not prompt Ankara to withdraw from the region. Instead, several areas of cooperation launched in the early 1990s continue to offer avenues for further development in partnership with the region’s governments. The potential for collaboration is greatest in the spheres of culture, trade and investment, and – to some extent – security.

Although the pan-Turkic ideology has been vehemently rejected in Central Asia, Turkey has a status of its own in the region’s cultural and educational sphere. For decades, Turkish TV channels have been accessible in the region, and Turkish scholarship programmes have enabled thousands of Central Asians to study in Turkey. In addition, Ankara has been successful in education export: private schools, especially those associated with the Gülen movement,[4] were genuinely popular due to their high level of education before facing marginalization due to either domestic or Turkish pressure. Ankara has tried to replace the Gülen schools with education institutes operated by the Maarif Vakfı, a state-led organization working in tandem with the Diyanet, Turkey’s massive Ministry of Religious Affairs. Furthermore, Ankara has systematically promoted collaboration under the auspices of the Turkic Council, of which Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and – since 2018 – Uzbekistan are members. Turkmenistan, following its Doctrine of Positive Neutrality from 1995, is an observer, but has become more involved recently.

In terms of economic relations, Turkey’s trade ties have significantly increased during the last fifteen years. Turkey’s exports to Kazakhstan increased from $460 million in 2005 to $979 million in 2020, and to Kyrgyzstan from $90 million to $416 million in the same period. In 2020, Turkmenistan imported products worth $786 million, compared to $181 million in 2005, while Uzbekistan has become the main Central Asian destination for Turkey’s exports. From 2005 to 2020, Uzbekistan’s imports from Turkey increased from $151 million to $1.15 billion.[5] The new economic development model introduced by President Mirziyoyev in 2016 rests on the opening of the market and fostering better relations with the international community to attract capital and investment.

However, although an increasing trend, these numbers show that compared to other states, most notably Russia, China and the EU, Turkey’s trade ties with Central Asian states are still relatively modest. In 2019, its trade with Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan accounted for less than 3% of Turkey’s total trade volume with the world, whereas among Central Asian countries, trade with Turkey outweighed Russia and China only in Turkmenistan’s import sector.[6] Yet again, the growth in the number of Central Asians, especially Turkmens, looking for work in Turkey rather than in Russia, and the region’s states’ dependency on the remittances they make, generate another potential driver of economic rapprochement.[7]

Since the second Karabakh war, Central Asian countries have demonstrated much interest towards Turkish military equipment, first and foremost its combat drones. Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan have been reported as planning to purchase the new generation Bayraktar TB3 drones, while Turkmenistan showcased its TB2 in a military parade in September 2021. Turkish entry to the Central Asian arms market is significant given Russia’s long-term dominance in the military sphere, Turkey’s NATO membership, and the protraction of intra-regional rivalries that drives the procurement of weaponry. What is more, co-operation in the security sector goes beyond the arms trade, with joint exercises and declarations over strengthening military collaboration being voiced from all four Turkic republics in the region.[8] After the weakness of Kyrgyzstan’s defence was demonstrated during the spring 2021 border conflict with Tajikistan, Bishkek – a member of the Russia-led Collective Security Treaty Organization – turned to Ankara, a NATO member, requesting regular military-technical assistance to help modernize the Kyrgyz armed forces and enhance their defence capabilities.

The willingness to develop ties with one another in various spheres can be interpreted as one manifestation of the preference for a diversified foreign policy, sought by both Turkey and the Central Asian states. Although Central Asian states’ multivectorism more often represents desire rather than reality, all Central Asian states have been successful in independent decision-making in relation to China, Russia, and the United States.[9] As for Turkey, its role in facilitating Azerbaijan’s victory in the second Karabakh war of 2020 seems to force Armenia to increasingly seek normalization with Turkey, even if it tries to gain enhanced security guarantees from Russia. Furthermore, Ankara’s activism in various conflicts from Syria to Libya could be taken as a sign of its increasing ability to shape international politics, making Turkey an attractive partner for the Turkic republics.

Limits to Turkey’s rise in Central Asia

Collaboration between Turkey and Central Asian states is intensifying, but there are factors that curb the process. First, although Turkey and Russia are strengthening their collaboration, Russia continues to view Central Asia as its sphere of interest and remains aware of Turkey’s NATO membership. As a result, Russian foreign policy experts have warned against the intensification of Turkey and Central Asia’s cooperation in the sensitive security sphere, framing it as being at odds with Russia’s interests.[10] It is, however, also possible that Moscow is not uncomfortable with Turkey’s NATO membership per se, given Ankara’s tendency to cause trouble inside the Alliance. Russia’s resistance to Turkey’s expansion into the Central Asian arms market might in fact be dictated by economic competition rather than security concerns. Central Asian governments, for their part, may deliberately showcase offers from Turkey to get better deals with Russia. If Russia resists increased security cooperation between Turkey and Central Asia, it changes the calculus of the collaboration’s rationality, regardless of the convergence of the bilateral interests of Turkey and the region’s governments.

The limits of Turkey’s influence in the security realm are also observable in Central Asian states’ intensification of their security cooperation with both Russia and China in response to the Taliban takeover in Afghanistan, thus indicating their preferred security partners at a time of acute regional conflict regardless of their continued procurement of Turkish weaponry. Although Turkey has offered itself as an actor able and willing to mediate between the Taliban and the West, Pakistan and Qatar have – at least by now – been more successful in their international mediation efforts. Ankara is still negotiating with the Taliban regarding the civilian administration of Kabul Airport, but its Afghanistan diplomacy seems to be aimed solely at elevating its status in the eyes of the US.

Second, in the sphere of trade, the potential for mutual economic benefit remains limited. Central Asia’s rail and road infrastructure is still underdeveloped. Although Turkey is eager to improve the region’s transport network, the connectivity domain is dominated by China, following its own interests and capacity. At present, Turkey’s trade with Central Asia goes through Iran both by road and by sea, which is a major point of vulnerability for Ankara given its difficult relationship with Tehran. Moreover, Ankara’s ability and political will to invest in Central Asia is limited due to Turkey’s current economic state and its funding commitments elsewhere in the world.

Third, the concentration of power in Central Asian leaders’ hands is a double-edged sword. It can speed up the process of rapprochement with Turkey because decisions can be made and implemented quickly, at least in the relatively ‘strong’ states of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. Yet the personalism of Central Asian regimes can also halt cooperation and jeopardize Turkey’s investment in the region. For example, the region’s governments’ eagerness to assert their sovereignty has complicated the development of the supra-national collaboration that is necessary for improving the intraregional trade connectivity from which Turkey hopes to gain economically. Improving Central Asia’s regional integration and connectivity is arguably in everyone’s interests. This includes the EU and the US, which in the context of strategic competition with China might even seek avenues for cooperation with Ankara in terms of connectivity projects, if not immediately then at least in the longer term.

Moreover, the quest for sovereignty in Central Asia has been coupled with the rise of nationalist sentiment, generating disapproval towards both pan-Turkic narratives and attempts to interfere in the countries’ domestic affairs. It is therefore rational that in its current engagement with Central Asian governments, Turkey refrains from intervening in their internal affairs. The known exception is Turkey’s attempt to arrest those affiliated with the Gülen movement and its school network, still in place in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. Most recently, Orhan Inandi, a Turkish-Kyrgyz dual citizen and a former educator in a school affiliated with the Gülen movement, was detained by Turkish National Intelligence Agency officers in Kyrgyzstan. Although Bishkek summoned the Turkish ambassador to protest the abduction, Kyrgyz State Committee for National Security chief Kamchybek Tashiev maintained that Turkish authorities had the right to prosecute Inandi given his Turkish citizenship.

A final point of tension between Turkey and the Central Asian governments has to do with their diverging approach to political Islam. During the past ten years, Erdogan has aligned with domestic Islamic groupings, funded Islamist militias, and supported jihadi factions in Syria and Libya. If in the 1990s Turkey and the Central Asian governments were politically out of sync due to Turkey’s promotion of democracy, nowadays the discrepancy is rooted in the approach towards religious groups. In Central Asia, Islam is applied as a legitimation tool and ingredient of national identity. Yet since Islamist movements have presented the biggest challenge to the secular authoritarian governments, the activities of Islamist non-state actors have been treated with extreme suspicion, and members of Islamist groups have faced systematic repression.

What was previously complicating Turkey’s relations with Central Asian governments was Ankara’s policy of offering a safe haven for Central Asian dissidents. Yet it now looks like Ankara is willing to cooperate more closely with the region’s governments and to arrest activists residing in the country. This is one of the outcomes of Turkey’s authoritarian shift that has brought its political system closer to those of the Central Asian states and generated potential for closer relations. However, the new authoritarian likeness has a downside. While it seems apparent that Turkey no longer treats Central Asian leaders as junior partners, the de-institutionalization of Turkey’s foreign policy decision-making process as a part of the regime’s further autocratization and the lack of Central Asia specialists in Erdogan’s inner circle complicates Turkey’s sustained and strategic long-term commitment in the region.[11]

Moreover, Central Asian governments’ political support for Turkey has its limits: the governments have still not reacted to Erdogan’s pleas to recognize the breakaway republic of Northern Cyprus. This means that Turkey is thus paradoxically facing the same limits that it did in the 1990s when it failed to persuade the region’s states to back its position in the Eastern Mediterranean and elsewhere.

Conclusions

In November 2021, Ankara triumphantly announced the renaming of the Cooperation Council of Turkic Speaking States as the Organization of Turkic States. The new name was one of the outcomes of the eighth summit of the Turkic Council, aiming to launch the body’s transformation from an informal cultural association into a political and economic organization. The upgrade of the Turkic Council was yet another demonstration of Turkey’s new activism in Central Asia, to which the region’s governments have responded with clear interest.

Turkey’s search for increasing strategic autonomy and the Central Asian states’ preference for a multivector foreign policy that would enable them to resist any single power’s dominance is the single most important long-term factor bringing Turkey and the region’s states into closer cooperation. Ankara’s lack of robust economic strength and its foreign policy overstretch nevertheless mean that the opportunities for Turkey’s rise are limited. In addition, although both Turkey and the Turkic republics often speak warmly about bilateral relations based on shared ethnic and cultural heritage, Turkey remains just one option among others as the region’s states attempt to diversify their foreign policy choices.

Endnotes

[1] Marlene Laruelle & Sebastien Peyrouse, Globalizing Central Asia: Geopolitics and Challenges of Economic Development (Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe, 2013), 76. Turkey’s provision of aid was also driven by its support for Central Asia’s Tatars, who had been deported from the Caucasus and Crimea and sought to return to their homelands.

[2] It is notable, however, that following the policy of “strategic depth”, Ankara initially sought to foster good relations with all of its neighbours, even Armenia. It was only later that the policy became more combative and assertive, subsequently souring Turkey’s relations with the regional powers. See Ali Askerov, ‘Turkey’s “zero problems with neighbors” policy: Was it realistic?’, Contemporary Review of the Middle East, 4(2), (2017): 149–167, http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncg/f/A_Askerov_Turkey_2017.pdf.

[3] These plans for the Caspian Sea region have triggered an angry response from Moscow given that they threaten Russia’s dominance over the Caspian gas market. If the plans were to materialize, Moscow would likely increase its pressure on both Turkey and the Central Asian Republics. See Natalia Konarzewska, ‘The “Dostluk” Deal: Boosting Pan-Turkic Energy Cooperation’, Turkey Analyst, 1 June, 2021, https://www.turkeyanalyst.org/publications/turkey-analyst-articles/item/666-the-dostuk-deal-boosting-pan-turkic-energy-cooperation.html.

[4] Fethullah Gülen, living in self-imposed exile in the United States, is accused by Ankara of ordering the 2016 attempted coup against President Erdogan.

[5] Azimzhan Khitakhunov, ‘Trade between Turkey and Central Asia’, Eurasian Research Institute, 2020, https://www.eurasian-research.org/publication/trade-between-turkey-and-central-asia/.

[6] ‘Turkey’s Central Asia policy’, Strategic Comments, 27:3, (2021): v–vii.

[7] Khamza Sharifzoda, ‘To Russia or Turkey? A Central Asian Migrant Worker’s Big Choice’, The Diplomat, 2 January, 2019, https://thediplomat.com/2019/01/to-russia-or-turkey-a-central-asian-migrant-workers-big-choice/.

[8] See e.g. ‘Turkish, Uzbek defense ministers sign military agreement, underline further defense cooperation’, Daily Sabah, 27 October, 2020, https://www.dailysabah.com/politics/diplomacy/turkish-uzbek-defense-ministers-sign-military-agreement-underline-further-defense-cooperation.

[9] Alexander Cooley, Great Games, Local Rules: The New Great Power Contest in Central Asia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

[10] See e.g. the comments in Vladimir Kulagin, ‘Vybyt’ iz-pod vliyania Rossii’, Gazeta.ru, 5 July, 2021, https://www.gazeta.ru/politics/2021/07/05_a_13703324.shtml?updated.

[11] Turkey’s Central Asia policy, Strategic Comments, 27:3, (2021): vii