Euroopan unionin ja Yhdysvaltojen on aika muodostaa yhteinen, kolmansia maita koskeva positiivinen talouspoliittinen ohjelma, joka hyödyttäisi kaikkia osapuolia. Se rakentuisi kahdenvälisille suhteille, muttei keskittyisi yksinomaan niihin. Ohjelma edustaisi EU:n ja Yhdysvaltojen yhteistä linjaa, vaikka osapuolilla olisikin ajoittain keskenään eriäviä syitä tukea sen eri osa-alueita.

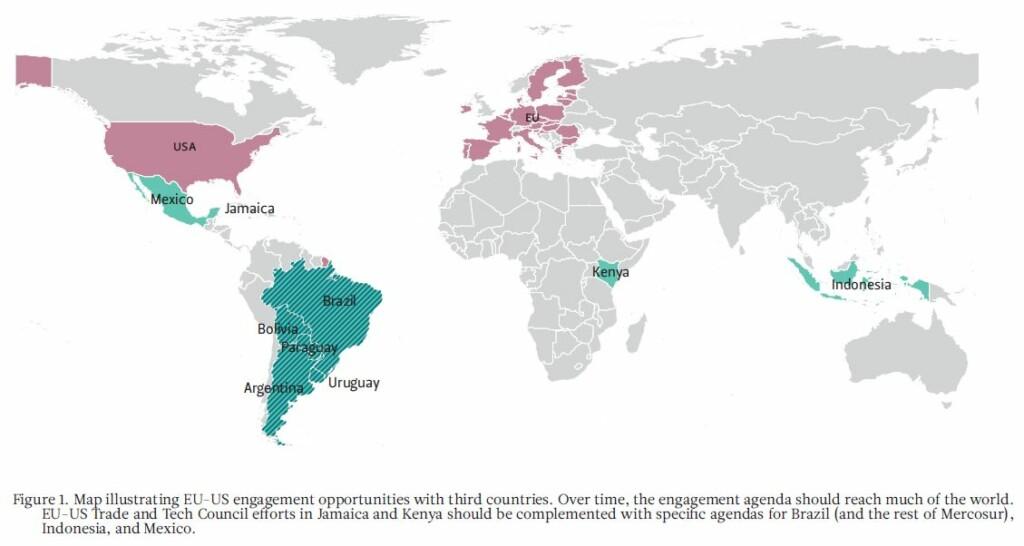

Ensimmäisiä merkkejä yhteisestä talouspoliittisesta ohjelmasta on nähtävissä EU:n ja Yhdysvaltojen kauppa- ja teknologianeuvoston hankkeissa Jamaikalla ja Keniassa. Poliittinen aikaikkuna Yhdysvaltojen ja EU:n lähentymiselle sekä uusille EU:n kauppasopimuksille saattaa kuitenkin sulkeutua vuonna 2024.

Tulevaisuudessa yhteisten aloitteiden tulisi ulottua suuriin talouksiin, kuten Brasiliaan, Meksikoon ja Indonesiaan. Sekä Washingtonissa että Brysselissä prioriteettilistan kärjessä pitäisi olla EU:n ja Mercosur-maiden välisen kauppasopimuksen voimaantulo.

Yhdysvaltojen ja EU:n tämänhetkistä suhdetta luonnehtii osapuolten etääntyminen toisistaan teknologian sekä teollisuus- ja ympäristöpolitiikan aloilla. Jotta lähentyminen olisi mahdollista, Yhdysvaltojen täytyy arvioida uudelleen ylimitoitettuja pelkojaan EU:n sääntelyvallasta – ja alkaa suhtautua eurooppalaisten standardien leviämiseen keinona saavuttaa yhteisiä päämääriä.

Introduction

Hopes for the EU-US Summit on 20 October 2023 were not high, yet the parties still managed to underdeliver. There was no agreement on critical minerals or a long-term resolution to steel and aluminium tariffs. Also lacking was an image of what the world would look like once both Brussels and Washington had completed “de-risking” and “diversifying” away from Beijing. While the parties spoke in detail about the actions taken against Russia, they were more concise on the tangible actions taken to engage with the rest of the world.

The stakes for cooperation between the European Union and the United States are high, due in large part to the head start that China has had with its now decade-old Belt and Road Initiative and the expansion of the BRICS grouping. To make things even more challenging, EU-US cooperation needs to be developed in the context of a United States that no longer seeks to negotiate new trade deals, preferring more ambiguous partnership frameworks. Similarly, if not quite as clearly, Europe’s interest in trade is waning, as opposition to further deals grows. However, even if US and EU interests do not always align in traditional trade policy aspects, they are clearly shared when it comes to international regime building and the broader geopolitics of technology and industry. This means that Washington and Brussels need to pursue cooperation in ways that do not immediately meet the eye.

This Briefing Paper argues for further geoeconomic alignment between the EU and the US. There is a need for both parties to build a shared, positive economic agenda that would engage the rest of the world in a way that is beneficial not only for them but for third countries as well. Furthermore, doing more together should not only result in a better individual outcome for each party but also help alleviate some of the pain points in the bilateral relationship.[1] The paper examines arguments for and against such an agenda and discusses opportunities for deeper EU-US engagement, highlighting the case of the EU-Mercosur free trade agreement as an example.

Arguments for and against a shared agenda

The proposed new economic agenda shared by the EU and the United States would build upon the bilateral relationship but not focus on it. It would be a positive agenda consisting of measures that not only Brussels and Washington but also third countries can see as beneficial. This contrasts with a negative economic agenda of sanctions, for example. Consequently, a positive EU-US agenda will supplement and balance a negative agenda of divestments from the economies of countries that Brussels and Washington see as hostile to their interests. It would also be shared between the EU and the US, even if they will often have distinct reasons for supporting different elements of it. Much can be done together through engagement with the outside world without resolving all bilateral economic (or other) issues.

One argument against such a shared engagement agenda is that it is not necessary. This argument rests on the supposition that EU and US capital will seek out the best opportunities without any politicians or bureaucrats nudging it to do so. It is the negative exceptions to a generally free flow of trade and investment on which governments should focus their attention. It is in this context that coordinated or cooperative policy — whether similar in substance or objective — must be justified.

The first counterargument to the argument above is the growing dysfunction of the World Trade Organization (WTO). This reality forces countries to plot win-wins just as they devise controls and means to keep powers inimical to their interests in check. The WTO is still necessary, but it is also increasingly inadequate when it comes to ensuring cooperation in tomorrow’s world economy. As a result, similar attention should be paid to policy detail on the positive, engagement side of the ledger.

The second counterargument focuses on the reality of the divergence between the United States and Europe, which is, by now, an established trend. Such divergence is evident in different regulation, different approaches to technology and environmental classifications, and both established ways to decarbonize Europe’s economy such as the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) and more recent innovations such as the brand-new Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). Meanwhile, the US refuses to renounce the use of tariffs even amongst friends, while its federal industrial policy packages run at more than a combined trillion dollars. Countervailing packages by European national and sub-national governments also pose a significant challenge to the integrity of Europe’s Single Market.

The third counterargument is that geoeconomic understanding cannot be limited to the defensive screening of investment or the offensive posing of sanctions; it should be employed in the pursuit of more positive goals. Prompted by the impacts of Covid-19 and Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, the 2020s have witnessed the growth of geoeconomic capabilities and coordination. In particular, the EU has shown itself capable of developing and implementing new instruments in the face of grave danger, such as those aimed at minimizing the use of Russian fossil fuels and at preventing Russian acquisition of dual-use goods from third countries. Similarly, the coordinated actions taken by the EU, the US, and partners against the Central Bank of Russia have demonstrated an enhanced capacity for action. This capacity should now be put to positive uses in engagement with third countries.

The EU-Mercosur case as a US interest

The most imminent issue on the shared engagement agenda is the future of Mercosur, a trade bloc led by Brazil but also featuring Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay and, as of December 2023, Bolivia as full members, and its trade deal with the EU.[2] Such a deal had already been negotiated once before in 2019, but has been under further negotiation in 2023 to satisfy Europe’s environmental demands. A ratified agreement would mean increased and preferential European access to the many natural resources in Mercosur countries, ranging from food to fuel, both fossil and renewable. A ratified agreement could also help diversify the Mercosur countries’ increasing trade orientation towards China and help ensure that Washington’s European allies are wealthy enough to increasingly contribute to their own defence.

If EU-Mercosur is not ratified, the United States will have greater cause for concern about the current trend of the approximation of Mercosur countries with China. Without an agreement, Washington should also expect to continue to bear more of the burden for Europe’s resource security, as it did in 2022. In its comments on EU-Mercosur, the US has so far focused on the possible detrimental impact of the spread of Europe’s “precautionary principles”. In the words of the US Department of Agriculture, the spread of these principles and related provisions “represent a major win for the EU in the arena of global norms, especially since the United States generally considers the Mercosur countries to be like-minded on the importance of science as a basis for trade and regulatory matters”.[3]

While Washington frequently worries about the “Brussels Effect”, or the spread of European standards, such anxiety can be a result of misunderstanding.[4] For example, Brussels’ refusal to negotiate on privacy means that digital standards are less central in EU trade agreements than, say, in the US-Mexico-Canada agreement (USMCA). While worries about losing out on EU import quotas for US products are legitimate, concerns about the spread of EU norms seem particularly small-minded at a time when Washington shows no interest in new trade agreements. The best Washington can do then is to seek by proxy the broader geostrategic benefits of such agreements.

The EU can serve as a proxy, for example, for Paraguay’s continuing recognition of Taiwan (Republic of China or ROC), as one of 12 UN member states to do so. Yet Paraguay has also considered shifting recognition to the People’s Republic of China (PRC), an issue that was also discussed during its 2023 presidential election. In the event, Santiago Peña, the pro-ROC candidate, beat off pro-PRC forces, including the powerful agricultural lobby looking to establish trade ties with the world’s biggest buyer of food. Since then, he has put pressure on the EU to ratify its agreement with Mercosur by underlining how the back-and-forth with the EU must come to an end, or else he will focus on other regions.[5] Similarly, Peña has voiced openness to other bloc member states to go ahead and negotiate an agreement with Beijing and, at the very least, has encouraged the bloc to turn towards Asia. A trade agreement with Beijing has been an expressed goal of Uruguay, but also something that both Brazil and Argentina have entertained at different times.

A US nudge may help prevent EU-Mercosur from unravelling, but whether it will be enough remains to be seen. It is not only the ultimatum from Paraguay that suggests the agreement is hitting a wall. The Mercosur-minded Spanish presidency of the Council of the EU ends in December 2023, and the agreement dates back to 2019, itself a different era. As the agreement ages, the EU may have to ask itself what exactly the Union is good for. If this deal cannot be brought into force, Brussels and the EU may well face an identity crisis: decades of work on the Mercosur agreement will have been wasted, and the EU may emerge as something other than the agreement-making superpower it has proved to be.

Other opportunities for engagement

Some examples of a positive shared economic agenda already exist. The clearest of these were the result of the 2022 ministerial meetings of the EU-US Trade and Technology Council (TTC). The EU and the US committed themselves to providing information and communication technology and services to third countries, starting with Jamaica and Kenya. Instead of simply counselling or exhorting these or other countries to avoid the use of Chinese providers in their network infrastructure, such positive projects offer a viable path forward. Yet Jamaica and Kenya are much smaller economies than Brazil or other G20 countries for which Washington and Brussels might develop a shared engagement agenda. Such countries of geoeconomic interest include, for example, Mexico and Indonesia.

Mexico presents a complicated picture. While 80% of its exports flow to the US and it is the nearshoring destination of choice for US capital, its relationship with American capitalism is increasingly difficult. Its current president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), has overseen a rapid militarization of Mexico’s economy as well as subjected private capital to expropriations. This has included challenging European interests in the country, especially those of Spanish energy giant Iberdrola, whose assets have been a target of AMLO’s self-proclaimed “new nationalization”. At first sight, this does not present a case for further European investment or other commitments to Mexico. However, on closer inspection, Europe can do much to aid Mexico’s development, beginning with ratification of the updated EU-Mexico free trade agreement.

The EU can also help Mexico secure a crucial natural resource and, by extension, alleviate tensions on the US-Mexican border: Currently, Mexico relies on US exports for most of the natural gas it consumes, while natural gas itself is around half of the country’s energy mix.[6] When US domestic demand increases, as it did in winter 2021, in Mexico, this foreshadows both economic trouble and death due to exposure to the cold. If European companies — with the explicit support of Brussels and relevant national capitals — were to develop the Mexican natural gas sector, they could accomplish much for Mexico and themselves. They would free up more Texan natural gas to be transmitted not south of the border but to Europe, where storage capacity is many times greater than in Mexico. Thus, Europe would also help secure its own supply of natural gas, a fuel that until recently flowed from Russia. While Americans may increasingly resent having to underwrite European energy security with other countries’ resources, US policymakers should see much to gain from shipping domestic resources.

Both Brazil and Mexico have strong ties to Europe and are also cases in which direct investment or economic engagement from the US are likely to come under greater scrutiny. It is therefore in Europe’s interest to engage when the US is perceived as acting ham-handedly. Meanwhile, Washington should be able to look beyond its trade quotas and examine European trade deals and their impact on a more enlightened plane. Thinking of Brazil as a competitor in agriculture, ethanol, and aviation — or Mexico in a range of manufacturing fields — is short-sighted in a world of geo-economic blocs. However, as such a shift will not come about easily, it may make most sense to introduce a geographic case that is pretty much equidistant from both Brussels and Washington, and therefore less likely to be subjected to mutual squabbling.

The obvious test case here is Indonesia, a country of around 280 million people, and by far the largest member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Both Washington and Brussels have longstanding yet thus far ineffectual plans to approximate themselves with Jakarta. Even combined, the EU and the US trade less goods with ASEAN as a whole than China. This is the case even though relations with shipping and financial centre Singapore and manufacturing hub Vietnam have been high on the agenda of both Brussels and Washington. The EU finds itself in an ongoing dispute with Indonesia over nickel and palm oil, the country’s leading commodities, and as a result Indonesia’s President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo has accused Brussels of “dictating” and “assuming that their standard is better than others”.[7]

Meanwhile, the US inaugurated a new stream of foreign policy and defence dialogues with Indonesia in October 2023, including a reaffirmation of Washington’s commitment to modernize Indonesia’s armed forces. To take approximation with Jakarta further, a broader form of economic engagement with Indonesia should be a shared goal of both Brussels and Washington. Indonesia’s decision not to join BRICS demonstrates an openness to such engagement and a wariness of Chinese alternatives.

The road ahead

Developing a shared positive economic agenda will not be easy, with challenges ranging from the most fundamental to more technical matters:

Competition. At the extreme lies a view of Brussels and Washington not as partners but as fierce competitors. This viewpoint is often voiced by battered veterans of numerous trade wars, ranging from aviation to the Trump presidency’s steel tariffs, or witnesses to Europe’s regulatory reach in respect of US technology companies. This way of thinking fails to acknowledge that today’s geoeconomics requires not only a different toolkit but also rhetoric. If someone is described as a fierce competitor in one realm of politics, it may easily spill over into other arenas. Such voices gained some credibility in the initial European reaction to the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and its broad-based subsidies for US manufacturing. The arrival of Europe’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) has been handled with more finesse, resulting in more US curiosity than condemnation. Going forward, it is vital to cooperate with allies and partners whenever such policies are planned, not least to prevent “protectionist chain reactions”.[8]

Autarky. Slightly less serious, but still a significant challenge is a push towards autarky in the United States or “strategic autonomy” in Europe. Some in Europe push for strategic interdependence with middle powers as an answer to economic insecurity.[9] Such partnerships may not always directly benefit the transatlantic alliance, but they should also not run counter to them. For example, it is critical that Brussels and Washington continue to align their policies when seeking raw materials from third countries rather than squeezing each other out of markets, or inadvertently triggering a race to lower standards. On the other hand, the development of a larger project such as the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) presents an opportunity to align priorities and action. Still, the risk that the pursuit of economic security will lead to an uncontrollable scramble for resources remains significant.

Money. Economic corridors need funding to be credible. The Global South perceives that the G7’s Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII), to which the Global Gateway is the EU’s contribution, is too often a mere rebranding of existing efforts. Nor is the promised USD 600 billion being leveraged at the pace of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. If the low-end estimate is correct, China has invested at least a trillion dollars in its BRI. In an unflattering albeit oft-heard comparison, the US and its allies are estimated to have spent several trillion dollars on the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. With China not having to rally to the defence of treaty allies and other partners, it is expected to hold a distinct advantage over the US in its ability to focus its attention and resources on infrastructure and supply chain projects around the world. Europe, too, is increasingly short on focus due to its commitment to Ukraine and the need to rebuild its own defences.

Venue. It is not clear where exactly the kind of coordination required by a shared engagement agenda should take place. Often the answer to this question does not seem to be a bilateral but rather a broader venue: the G7. Many in Brussels believe that by prioritizing a venue that also includes Canada, Japan, and the United Kingdom, it is less likely that conversations will descend into bickering over bilateral issues. However, for more targeted shared interests, such as the case of Mercosur highlighted above, something else is needed. Thus far, the TTC has served for smaller projects, but novel thinking requires significant participation by Secretaries from Washington and Commissioners from Brussels as well as some institutional innovation. Both parties must rise above their perceived, sectoral short-term interests to offer the world a better deal than China is currently offering, as a growing number of countries struggle to repay Beijing debts they have incurred.

Window. The world needs to be ready by spring 2024. That is the message from both Washington and Brussels with the US general election and the European Parliament (EP) elections occurring in the coming year. An election year always brings change, but this time around it also means that the political window for trade agreements may well be closing in Europe with the prospect of a more agrarian-minded Parliament. In the US, the return of Donald Trump – or even just a more similarly minded House of Representatives – will make any engagement with the outside world more challenging and the life of overseas allies unpredictable. This means that while the current moment may not seem like the most promising time for EU-US cooperation, less promising times may lie ahead. To keep the window open, more work needs to be done now.

Concluding thoughts

This paper has argued that the EU and the United States need a shared, positive economic agenda for the world. The negative agenda of recent years has built capacity and can serve as an example of new levels of coordination for an engagement agenda that can not only rival China’s Belt and Road Initiative, but more broadly allow for more serious geoeconomic approaches. The need for such an agenda is ever more pressing as the wars in Ukraine and Gaza continue to drive wedges between most Global South capitals on the one hand, and Washington and Brussels on the other. While the conflicts complicate initial phases of outreach, they also demonstrate how the rest of the world already sees the EU and the US working in tandem. Why not also work together on a more positive agenda for third countries?

While a broader G7 agenda can be helpful, it should not replace closer coordination between its two biggest economic blocs. Such coordination must also recognize that the US and the EU often have the same objectives but for different reasons. The ability to live with that dissonance is a necessary skill to be harnessed in today’s strategically challenging global economy. However, if such objectives are not determined, much can be lost not only in terms of the economy but also in terms of the broader geostrategic alignment of the Global South. Finally, by working together on a vision for the world, Washington and Brussels may also set the transatlantic partnership on a new course, as their interests increasingly converge.

For Washington, this means that it should look at EU trade agreements in terms of how the EU can help draw other countries closer to itself (rather than China), and how the resulting trade can make the EU more secure. Such a European Union will have greater security of supply, be better able to defend itself against potential aggressors and challengers, and contribute to US global security efforts.

Endnotes

[1] This hypothesis was also shared by many experts during background conversations for this paper, which took place in Brussels and Washington in autumn 2023. The author wishes to thank all interlocutors for the contributions.

[2] On the longer EU-Mercosur trajectory and its role in engaging and attracting Brazil, see Wigell, Mikael (2015) “Seal the Deal or Lose Brazil: Implications of the EU-Mercosur Negotiations”. FIIA Briefing Paper 171. https://fiia.fi/en/publication/seal-the-deal-or-lose-brazil; and Tähtinen, Lauri (2021) “Engaging Brazil in the Era of Climate Action: Can Europe and the United States Devise a New Globalisation?”. FIIA Briefing Paper 319, https://fiia.fi/en/publication/engaging-brazil-in-the-era-of-climate-action.

[3] U.S. Department of Agriculture (2021) “EU-Mercosur Trade Agreement: A Preliminary Analysis”. International Agricultural Trade Report, 7 January 2021, https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/eu-mercosur-trade-agreement-preliminary-analysis.

[4] For an argument for working in tandem, see Orszag, Peter (2023) “Do not underestimate the ‘mega-Brussels effect’ of EU-US co-ordination”, Financial Times, 16 October 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/9173e128-b702-43cc-8c63-552a1dad4ac3. See also Bradford, Anu (2023) Digital Empires: The Global Battle to Regulate Technology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[5] Buenos Aires Times (2023) “Paraguay President Peña says it ‘does not matter who is elected’ in Argentina”. 24 October 2023, https://www.batimes.com.ar/news/latin-america/paraguayan-president-says-it-does-not-matter-who-is-elected-in-argentina.phtml.

[6] Berg, Ryan C. and Henry Ziemer (2023) “For North American Energy Security, Go Local: Examining the Role of Natural Gas and Mexico’s Energy Sector”. CSIS Analysis, 24 August 2023, https://www.csis.org/analysis/north-american-energy-security-go-local-examining-role-natural-gas-and-mexicos-energy.

[7] Quoted in Ferchen, Matt and Cheng-Chwee, Kuik (2023) “EU-ASEAN Trade Investment and Connectivity Cooperation”. Carnegie Europe, 4 July 2023, https://carnegieeurope.eu/2023/07/04/eu-asean-trade-investment-and-connectivity-cooperation-pub-90083.

[8] For how such chain reactions can occur and how they should be managed, see Wigell, Mikael (2023) “Managing the New Economic Security Dilemma”, HSF Blog, 16 November 2023, https://helsinkisecurityforum.fi/news/managing-the-new-economic-security-dilemma/.

[9] Aydıntaşbaş, Aslı et al. (2023) “Strategic Interdependence: Europe’s New Approach in a World of Middle Powers”. ECFR Policy Brief, 3 October 2023, https://ecfr.eu/publication/strategic-interdependence-europes-new-approach-in-a-world-of-middle-powers/.