While Indonesia still stands out as one of the stronger democracies in Southeast Asia, its democratic credentials remain flawed. Nevertheless, public support for the current administration has remained high thanks to sustained economic growth, welfare measures and large infrastructure projects.

Indonesia has continued to bolster its international status through ASEAN, even if its position is one among equals. Within the organization, Jakarta has aimed to play the role of democracy promoter and bridge-builder.

While China’s influence in the country has grown, Indonesia has sought a middle ground within the great-power competition, also pursuing partnerships with European countries, Japan, Russia, and the Gulf countries in order to diversify its political and economic relations.

This offers opportunities for the EU. However, Europe’s declining image in Indonesia, colonial history and perceived double standards are obstacles to strengthening EU-Indonesia relations.

Challenges remain for Indonesia in its quest to become a global player. The country will need to contribute solutions to both regional and global issues, and its hedging game and strategic autonomy in foreign-policy choices may become complicated due to increasing global expectations and responsibilities.

Introduction

Following Indonesia’s fifth presidential election on 14 February 2024, Prabowo Subianto will assume office in October this year. He will take up the reins over Southeast Asia’s most populous country with over 270 million people, which boasts the region’s largest economy, a young population, and an abundance of natural resources. Indonesia is a driving force in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), hosting the organization’s secretariat in Jakarta. Globally, Indonesia has strong ambitions to become a high-income country in the next few decades, and to carve out its own geopolitical role in the ongoing great-power competition.

As a leading member of the so-called Global South, Indonesia is a coveted partner for the major powers. The European Union is keen to take its relations with Jakarta to the next level, including through the completion of a Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA); the United States recognized Indonesia’s geopolitical importance by upgrading relations to the level of a Strategic Partnership in late 2023; for Japan, Indonesia is a Comprehensive and Strategic Partner sharing fundamental values and principles; and for China, Indonesia, which has signed up to Beijing’s Global Development Initiative (GDI), is an important partner in building “a community with a shared future for mankind”, the Chinese Communist Party’s official foreign-policy goal.

This Briefing Paper examines the underlying drivers of Indonesia’s rise on the global stage, arguing that the country’s increasing clout is rooted in economic growth underscored by a strong national identity discourse, a leading role in regional affairs, and a consciously equidistant geopolitical approach amid great-power competition.

A flawed democracy prioritizing domestic economic growth

Indonesia’s democracy has made significant strides but remains flawed. During the authoritarian regime of President Suharto (1967–1998), Indonesia’s military-based “controlled democracy” focused on achieving economic growth. In the 2000s, President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono established civilian control over the army, but only partially succeeded in breaking the oligarchs’ monopoly and improving civil society participation. His successor, Joko Widodo, popularly known as Jokowi, was seen as a reformer when he was elected in 2014, but some analysts contend that democratization stalled during his administration, with increased repression of critics and weakened anti-corruption measures. The Indonesian National Armed Forces (TNI) have left politics for good, which is exceptional in the Southeast Asian context, where generals often either run the country directly or pull the strings behind the scenes.

However, it is important to note that during Jokowi’s administration, the military have taken on a more prominent role in local politics and civilian life, particularly during the Covid-19 pandemic.[1] Furthermore, Jokowi handpicked President-elect Prabowo to continue his legacy, and, after some judicial manipulation to allow for this, pushed his son Gibran to become Prabowo’s running mate, resulting in accusations of political dynasticism. In addition, incoming President Prabowo’s record of authoritarian rhetoric, and allegations of human rights violations during his tenure as defence minister, have raised eyebrows among activists. Having said all this, Indonesia still stands out as one of the stronger democracies in a region beset by autocratic hardening.[2] While it remains to be seen how the state of democracy will evolve under Prabowo, it is unlikely that the dark days of Suharto’s iron-fisted repressive rule will return. For the near future, Indonesia is likely to continue to be classified as a flawed democracy.[3]

Throughout Jokowi’s decade at the helm, public support for his administration remained high thanks to sustained economic growth, welfare measures and major infrastructure projects such as the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed railway. GDP grew by 43% in ten years, and with the exception of the pandemic years of 2020 and 2021, Indonesia’s economy expanded at a rate of approximately 5% annually. By 2022, Jokowi had succeeded in making Indonesia an upper-middle income country. With a GDP currently amounting to an estimated 1.47 trillion USD, it is projected to become the world’s sixth largest economy by 2027. President-elect Prabowo has expressed the ambition to increase growth by 6–8% in order to put Indonesia on track to become a fully developed country and one of the world’s five largest economies by 2045.

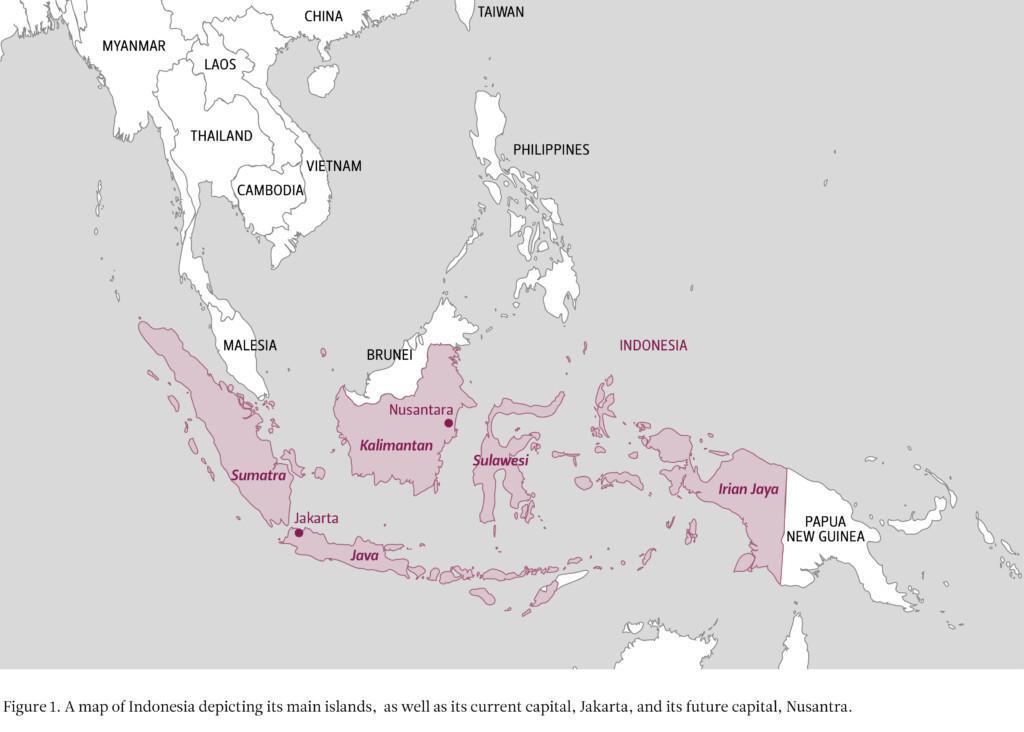

These ambitions were underscored by the start of accession talks in February this year to become the first country in Southeast Asia to join the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). As is obvious from Indonesia’s plans to join the OECD, its economy will need to adhere to strict policy standards and best practices, which can boost foreign investment. The Jokowi administration has also been investing heavily in the construction of the new capital, Nusantara, meaning “archipelago”, in the jungle on the thinly populated island of Kalimantan (see Figure 1). Seeking to become a “green and smart global city” based on sustainable and inclusive development and slated for completion by 2045, the new capital symbolizes Indonesia’s global economic ambitions well. Furthermore, in order to promote the diversification of the local economy and foster a domestic electric-vehicle (EV) supply chain, in 2019 Indonesia imposed an export ban on nickel, of which the country is the world’s largest producer. This invigorated the domestic metals and mining industry, and boosted Foreign Direct Investment from American, South Korean and especially Chinese firms.[4]

In addition to economic growth, Jokowi has successfully appealed to Indonesia’s national identity in order to promote cohesion. Indonesia is the world’s largest Muslim country, with 87% of its population (242 million) Muslim and 11% Christian (29 million). Religion is strictly regulated, with blasphemy laws and the suppression of minority religions. However, religion does not currently play an overtly strong role in mobilizing political support, as was also evident in President-elect Prabowo’s campaign.[5]

Nevertheless, religion is part and parcel of Indonesia’s national identity concept of Pancasila, which consists of five principles: monotheism, civilized humanity, national unity, deliberative democracy, and social justice. Pancasila is intended to alleviate the religious tensions of a multiethnic and multifaith nation and promote pluralism, based on the idea that a specific religious practice is an individual’s choice. Pancasila is also the source of the values and laws that regulate the governance of the state. Furthermore, Pancasila ideology is an essential component of the Indonesian education system and is inculcated in its precepts.[6] One could argue that Pancasila is the glue that holds the vast and populous country together. Some Islamist activists contend that Pancasila is responsible for the rising number of conversions to Christianity and does not give Islam a sufficiently prominent place in Indonesian national ideology. As Indonesia has witnessed the rise of Islamist extremist activity and sentiment in recent decades, President Jokowi’s administration has focused on promoting Pancasila and Indonesia’s historically moderate version of Islam to confront this trend, and the president-elect has followed in his footsteps.

Regional stability through ASEAN: Indonesia as primus inter pares in Southeast Asian regional politics

Indonesia’s rise on the global stage is also driven by its regional aspirations. Under Jokowi, Indonesia has continued to bolster its international status through ASEAN, not least during the country’s chairmanship of the regional organization in 2023. Indonesia has contributed greatly to ASEAN’s long-term development, and is certainly a top contender for exerting regional leadership. Having said that, despite being overwhelmingly the largest and most populous state within the regional association, Indonesia has accepted a position as one among equals. As one of the founding members of ASEAN, Jakarta places the association at the centre of regional initiatives and diplomatic architecture. Hosting the ASEAN secretariat in Jakarta is one manifestation of this. Indonesia has also taken on the difficult task of mustering a consensus among ASEAN governments and staking out a common interest amid diverse views. In addition, befitting its role as the region’s most robust democracy, Indonesia has been a proponent of democracy and rules-based multilateralism through ASEAN’s many sub-regional institutions, such as the ASEAN Regional Forum and the East Asia Summit, which is the “premier political and security forum”.

Under Jokowi, Jakarta has played an active role in ASEAN, particularly in dealing with the Myanmar conflict. Indonesia’s special envoy carried out numerous engagements with different stakeholders in Myanmar and the region. Some analysts contend that the “non-megaphone” diplomacy that Indonesia practised was ineffective and unimaginative in leading ASEAN to try to resolve the Myanmar crisis.[7] High expectations were placed on Jakarta to be more muscular in dealing with the Burmese junta. In fairness to Indonesia, however, it should be noted that ASEAN has been divided on dealing with the junta, with Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore taking a tougher line than Thailand, Laos and Cambodia, which have closer military-to-military relations with Myanmar. Furthermore, while attempting to play the role of “good international citizen” and “democracy promoter” within ASEAN, Indonesia’s vision of being a “bridge-builder” in the region has resulted in Jakarta adopting a more conciliatory approach to the Myanmar conflict. At the end of the day, the way that the Myanmar issue was handled within ASEAN underscores the region’s sovereignty-conscious diplomacy when it comes to handling the various conflicts and crises facing the organization’s member states.[8]

Global ambitions as a Muslim powerhouse from the Global South

Indonesia is also emerging as a strong Muslim powerhouse, economically and geo-economically, but certainly also geopolitically. Indonesia’s announcement of accession talks to join the OECD, rather than BRICS, was therefore also interpreted as a political decision. Since 1948, the concept of “free and active foreign policy” (politik bebas dan active), introduced by then-President Muhammad Hatta, has been a guiding concept in Indonesia’s non-alignment. Indonesia has historically been a strong supporter of the self-disposition of small and middle powers, as symbolized by its organization of the Bandung Conference of Asian-African Countries in 1955. Also today, Jakarta has been aiming to retain strategic autonomy in its foreign-policy choices, without becoming overly reliant on one partner or another. Particularly under Jokowi, Indonesia has become critical of the West for failing to address inequality in the Global South, and has sought greater cooperation with China in an effort to find a middle ground amid the great-power competition.

The United States views Indonesia as one of the battlegrounds for influence in the great-power competition. Following the 2023 Comprehensive Strategic Partnership agreement, the sale of F-15 fighter jets to the Indonesian air force and maritime security cooperation signal deepening ties between Washington and Jakarta. At the same time, the Americans are concerned about Indonesia’s close ties with China on the economic front. According to a recent survey, Indonesian elites contend that China has become the preferred alignment choice, and that Beijing has both vast economic resources as well as the political will to provide global leadership.[9] China is Indonesia’s main trading partner, with petroleum, palm oil and iron ore being the main Indonesian export products. The Jakarta-Bandung high-speed railway is a flagship project of the Belt and Road Initiative. But while Beijing and Jakarta have good economic ties, they also have competing claims in the South China Sea, and there have been tense stand-offs between the two navies in the recent past. Pragmatic equidistance is a term that applies to Jakarta’s relationship with both Washington and Beijing.[10] This means that Indonesia cooperates with both the US and China when it serves its own interests. It is little wonder therefore that Indonesia is also seeking other partners from Europe, Japan, Russia, and the Gulf countries to diversify its political and economic relations.

Under President Jokowi, Indonesia’s “free and active foreign policy” translated into an independent and neutral policy line on Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. For Indonesia, the onset of the war threatened to disrupt Indonesia’s post-pandemic economic recovery and negatively impact both food security and weapons imports. In an effort to balance between Russia and the West, Indonesia has condemned the war in a measured way, without using the words “unlawful” or “invasion”, and without using the labels of aggressor or victim.[11] In 2022, President Jokowi engaged in diplomacy in Moscow and Kyiv, and then-Defence Minister Prabowo tried to negotiate an end to the war by proposing a peace plan. Indonesia’s approach to the invasion has been influenced by several factors: historical support from the Soviet Union after Indonesia’s independence, strong defence ties with Russia, a quest for greater equality and multipolarity, and perceived Western hypocrisy. Indonesia’s colonial history also plays a role – after all, the country suffered three centuries of Dutch colonial exploitation. Suspicions of foreign meddling are further driven by the fact that during the Cold War, separatist rebellions in resource-rich Indonesian provinces were fuelled by external actors in the ideological competition between the Soviet Union and the US.

Relations with the EU, and the road ahead

As is clear from the above, Indonesia can no longer be overlooked as a global partner, including for the EU, whether in terms of supply chain diversification, climate change mitigation, access to resources, trade or regional security. Importantly, Jakarta’s foreign policy objective of “paddling between two reefs” and charting its own strategic course offers opportunities for the EU to act as a third party for countries such as Indonesia that seek to hedge against the uncertainties of China-US rivalry. Trade between the EU and Indonesia is sizable, amounting to over €30 billion (EU imports from Indonesia were €18.4 billion in 2023, and exports €11.4 billion). Launched as early as 2016 and making slow progress, the free trade negotiations on the EU-Indonesia CEPA have entered their 18th round.

However, EU-Indonesia relations are suboptimal at the moment. First, the EU’s perceived influence and overall image in the region has declined. According to the opinion poll among Southeast Asian elites referred to above, levels of distrust towards the EU exceeded levels of trust in 2024, and 54% of Indonesian respondents were not confident that the EU would “do the right thing” to contribute to global peace, security, prosperity and governance, compared to 48% in 2023. At the same time, there has been an increase between 2023 and 2024 in the number of Indonesians who think that the EU is too preoccupied with its internal affairs, that its worldview is incompatible with Indonesia’s, and that the EU is not a responsible or reliable partner.[12] Worsened perceptions can in part be explained by Indonesia’s above-mentioned nickel export ban, which resulted in the EU filing a case at the World Trade Organization, as well as EU restrictions on palm oil imports from Indonesia. A good example of the deterioration in relations is Indonesia’s Minister for Economic Affairs accusing the EU of “regulatory imperialism” through its deforestation laws.

Furthermore, colonial history certainly plays a role in EU-Indonesia relations. It is little wonder that the legacies of past involvement by outside powers, including Europe, have made Indonesia sensitive to external criticism, whether regarding its state of democracy, or the clearing of forests for palm oil plantations and its connections to climate change. Hence, it is no surprise that there is suspicion about the motives of the EU in its dealings with Indonesia. Accusations of Western hypocrisy in the case of the Israel-Hamas conflict further compound relations with Europe. Indonesia accuses the West of double standards: the West expresses ire over the failure of Global South countries to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine but, at the same time, does not condemn Israel’s bombing of Gaza.

Nevertheless, the stakes are high, not least in view of Indonesia’s own ambitions as a global player. The “Golden Indonesia 2045 Vision” (Indonesia Emas 2045) sets out the country’s trajectory to becoming a major player in global affairs by the time of its centennial due to its economic size, great potential, and geostrategic position at the crossroads of the Indo-Pacific realm. Becoming a truly major player requires a foreign policy and strategy on how to realize such a vision. While joining the G20 club, and probably the OECD, points to Indonesia’s place in the global order, it still has some way to go before it can punch its weight. Being one among equals within ASEAN or being a “good global citizen” and “bridge-builder” is not enough, nor does sheer size count. Being a global player entails contributing solutions to both regional and global challenges, and thus far Indonesia has not exhibited any such traits, although this may change in the future.

Conclusions

As argued above, Indonesia is a middle power that is gaining global prominence both economically and politically, raising the stakes for other actors, including the EU. Currently, Indonesia has strong ambitions to become a developed country in the near future, and to play a pivotal role as a major global power. For now, Indonesia is hedging its bets. Hedging, whether policy or practice, is a typical trait of ASEAN middle powers such as Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, the Philippines and Singapore, and Indonesia is no exception. It has the capacity and resources not to choose sides or to become over-reliant on any external power. This results in complex relationships with external powers, which Indonesia skillfully navigates by avoiding manipulation and entrapment, while at the same time avoiding confrontations that are to its detriment. However, while Indonesia aspires to gain further clout as a major global player by joining various clubs such as the G20 and potentially the OECD, where important decisions are made, it will have to face up to the reality that membership in these clubs entails expectations and responsibilities. Whether Indonesia will be able to continue to play the hedging game and maintain a “one among equals” relationship within ASEAN remains to be seen.

Endnotes

[1] See e.g., Setijadi, Charlotte (2021) “The pandemic as political opportunity: Jokowi’s Indonesia in the time of Covid-19.” Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 57, no. 3, 2021: 297–320.

[2] Gaens, Bart and Olli Ruohomäki (2022) “Southeast Asian Democracy: Democratic Regression or Autocratic Hardening?” FIIA Briefing Paper 342. https://fiia.fi/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/bp342_southeast-asian-democracy.pdf.

[3] “Flawed democracy” is the term used by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) to characterize political systems in which elections are free and fair, and basic civil rights are honoured, but where issues remain in terms of media freedom infringement and political opposition suppression.

[4] Lakshmi, Anantha A. and Andy Lin (2024) “In charts: How the Joko Widodo era remade modern Indonesia’s economy”. Financial Times, 11 February 2024. https://www.ft.com/content/66a490e3-9268-4d8d-b7df-d2f901cd0fde. Far-reaching Chinese involvement has made the US government wary of pursuing a strategic materials deal with Indonesia. Korteweg, Rem and Vera Kranenburg (2024) “The good, the bad, and the ugly. Resource nationalism, geopolitics, and processing strategic minerals in Indonesia, South Africa and Malaysia”. Clingendael Report, May 2024, p. 1. https://www.clingendael.org/sites/default/files/2024-05/Report_Resource_nationalism_geopolitics_and_processing_strategic_minerals.pdf.

[5] Chaplin, Chris and Syarifuddin Jurdi (2024) “Faith, democracy, and politics in Indonesia: Explaining the lack of Islamic mobilisation in 2024”. LSE Research, 8 February 2024. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/religionglobalsociety/2024/02/faith-democracy-and-politics-in-indonesia-explaining-the-lack-of-islamic-mobilisation-in-2024/.

[6] Maulida, Siti Zahra, Xavier Murphy and Elliot McCarty (2023) “The Essence of Pancasila as the Foundation and Ideology of the State: The Values of Pancasila”. International Journal of Educational Narratives 1, No. 2, 2023, pp. 95–102.

[7] Idrus, Pizaro Gozali (2023) “As ASEAN chair, Indonesia was ineffective, unimaginative in Myanmar crisis: Analysts”. Benar News, 7 December 2023. https://www.benarnews.org/english/news/indonesian/indonesia-asean-chair-review-12072023143534.html.

[8] Parks, Thomas (2023) Southeast Asia’s Multipolar Future: Averting a New Cold War. London: Bloomsbury, p. 78.

[9] Seah, Sharon et al. (2024) The State of Southeast Asia: 2024 Survey Report. Singapore: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, pp. 48 and 67. https://www.iseas.edu.sg/centres/asean-studies-centre/state-of-southeast-asia-survey/the-state-of-southeast-asia-2024-survey-report/.

[10] Connelly, Aaron (2023) “Indonesia: Maintaining Pragmatic Equidistance”. In Conley, Heather A. et al. Alliances in a Shifting Global Order: Rethinking Transatlantic Engagement with Global Swing States. Berlin: German Marshall Fund, pp. 31–34. https://www.gmfus.org/sites/default/files/2023-04/Global%20Swing%20States_27%20apr_FINAL_embargoed%20until%202%20May%202023.pdf. The term “pragmatic equidistance” is originally from Laksmana, Evan A. (2017) “Pragmatic Equidistance. How Indonesia manages its Great Power relations”. In Denoon, David B.H. (ed.) China, The United States, and the Future of Southeast Asia: US-China Relations. New York: New York University Press, pp. 113–135.

[11] Kliem, Frederick (2024) “Not our war. What ASEAN governments’ responses to the Ukraine war tell us about Southeast Asia”. The Pacific Review 37, no. 1, 2024, pp. 211–243.

[12] Seah, Sharon et al. (2024) The State of Southeast Asia: 2024 Survey Report. Singapore: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, p. 59. https://www.iseas.edu.sg/centres/asean-studies-centre/state-of-southeast-asia-survey/the-state-of-southeast-asia-2024-survey-report/.