In the 2024 EU elections, far-right parties are expected to win more seats in the European Parliament than ever before. At the national level, too, far-right parties are entering more and more EU governments. Despite these gains, the centre-right European People’s Party, rather than the far right, is likely to play the central role in the EU institutions in the next legislature.

The EU’s consensus-based system is a safeguard against the sudden seizure of power by far-right parties. But once they have achieved a certain position, the same system makes it difficult for others to form majorities without them.

The EU is therefore facing not a sweeping but a creeping gain in far-right power, as centrist political parties become more open to cooperation, and far-right positions are slowly normalised in political discourse.

Paradoxically, the very mechanisms that are supposed to protect national sovereignty (such as unanimity requirements in the Council) are the ones most likely to allow far-right parties to influence EU policy, even if they represent only a minority of EU citizens.

Introduction

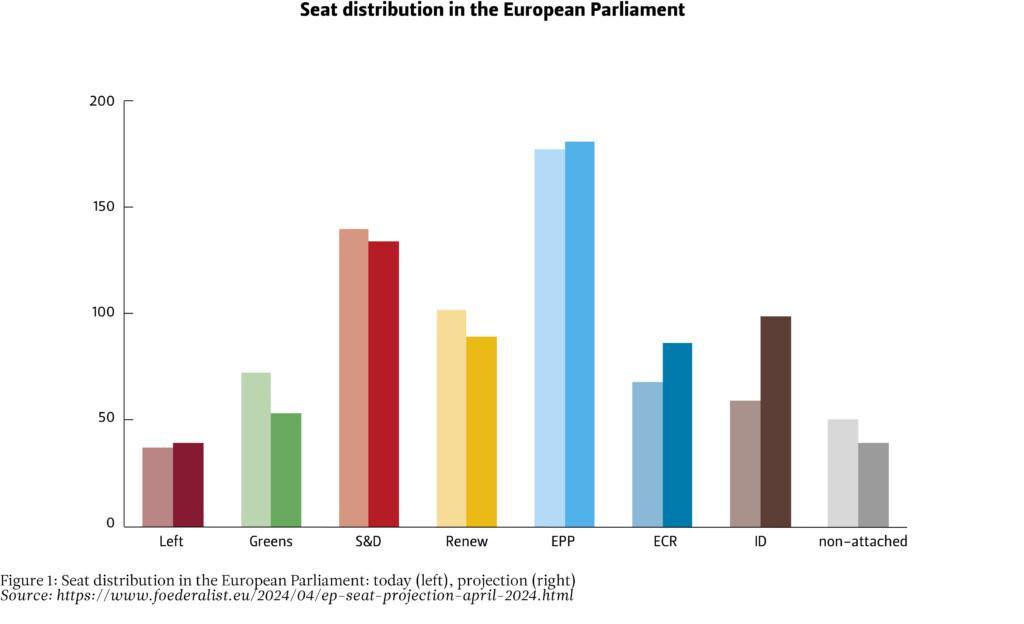

With a month to go before the EU elections on 9 June 2024, opinion poll-based seat projections forecast major changes in the composition of the European Parliament.[1] Far-right parties, which already fared relatively well in the 2019 elections, could further increase their vote share and exceed 25% of the seats for the first time. This success is likely to come at the expense of centre and centre-left parties, especially the Greens and the liberal Renew group.

But the surge of the European far right not only affects the European Parliament. As the number of member states in which far-right parties participate in government has increased in recent years, so too has the presence of far-right ministers in the Council of the European Union. This Briefing Paper takes a look at the expected party-political composition of the EU institutions in the 2024–29 legislative term and its implications for EU policy. How far will the rise of the far right go and what are its chances of exercising political power at the EU level?

Background: The far right in Europe

Far-right parties in the European Union have traditionally been organised in a number of EU-level organisations. Currently, there are two far-right groups in the European Parliament: the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR), and Identity and Democracy (ID). The ECR was originally founded by the British Tories and the Czech ODS as a relatively moderate, Eurosceptic conservative group. However, with the Tories leaving the group as a result of Brexit and more extreme parties joining, the ECR has moved to the right over the last decade and is now dominated by Giorgia Meloni’s Brothers of Italy and the Polish Law and Justice party (PiS). The ID group, on the other hand, has always represented the far right and includes parties such as Marine Le Pen’s National Rally from France, Italy’s Lega, and the Alternative for Germany (AfD).

In general, both the ECR and ID are internally heterogeneous and can partly be seen as alliances of convenience. Attempts to merge the two groups have repeatedly failed, in part because of rivalries between their members. However, membership of the ECR and ID has not been stable, with various national parties switching between them over time. This includes, for example, the Finns Party, which switched from the ECR to ID in 2019, and back again in 2023. Other far-right parties, most notably Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz in Hungary, are not currently members of either group.

Despite this, the two far-right groups have much in common with regard to core policy positions. Both take a hard line on migration, favour traditionalist gender policies, and reject ambitious climate action. Both tend to be pro-business, although neither has a very coherent line on economic and social issues. Both are hostile to supranational European integration, emphasise national sovereignty, and at most support intergovernmental cooperation between states. Both groups include some member parties that are openly pushing for their countries to leave the EU and/or have been criticised for not respecting the EU’s fundamental values of democracy, human dignity, and the rule of law. In view of these similarities, this paper refers to both groups as ‘far right’ and refrains from making further distinctions (e.g., between ‘conservative’ and ‘extreme’ right). The main policy difference between the two groups concerns Russia: while most ID parties have traditionally maintained good relations with the Putin regime and are reluctant to provide military support to Ukraine, the ECR advocates a hard line towards Russia and is generally NATO-friendly.

The two groups also differ structurally in terms of their government experience at the national level. While many ECR parties are or have been in government – either alone or in coalition, often with members of the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP) – ID has long been dominated by parties that have no executive experience and play the role of a ‘systemic opposition’, often leading to more populist and extreme rhetoric on their part. In recent years, however, ID member parties have taken part in national governments in Austria (2017–19), Italy (2018–19 and since 2021), and Slovakia (since 2023).

Finally, the ECR and ID have also been treated differently by the other political groups in the European Parliament. On the one hand, the centrist groups have maintained a cordon sanitaire towards ID, refusing any active cooperation on policy and excluding its members from influential parliamentary positions such as committee chairs. On the other hand, relations with the ECR have traditionally been less tense. Before the departure of the Tories, the centre-right EPP and the liberal Renew group cooperated with the ECR on many occasions, for example on trade policy. Since 2019, however, this alliance has not had a majority in the European Parliament, and the ECR’s shift to the right has made agreements more difficult.

European Parliament: Implications for majority building

As a co-legislator involved in almost all EU legislation, as well as in budgetary matters and the election of the European Commission, the European Parliament has long been an important power centre in the EU. Unlike most national parliaments, however, decision-making in the European Parliament is characterised not by stable coalitions but by flexible, issue-specific majorities.

In most cases, these majorities have always been based on cooperation between the two largest groups, the EPP and the Socialists and Democrats (S&D) – the so-called ‘grand coalition’, which is usually supported by the liberal Renew and/or the Greens. After the 2014 elections, the EPP, S&D and Renew groups gave this cooperation a more formal character through a memorandum of understanding, which was, however, terminated by the S&D in 2017. Nevertheless, cooperation between the three groups continued and was also decisive in the election of Ursula von der Leyen as President of the European Commission in 2019, giving rise to the term ‘von der Leyen majority’. In 2022, they adopted a joint programme of priorities for the remainder of the parliamentary term.

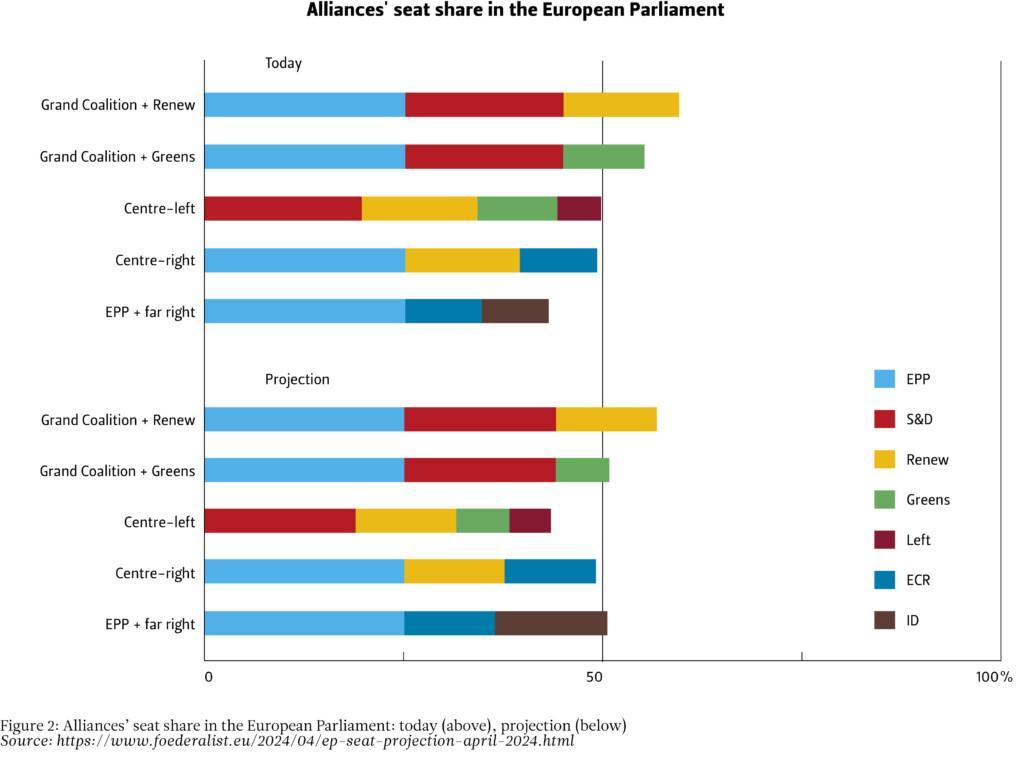

However, this ‘grand coalition’ has never been without alternatives. Some votes in the European Parliament have traditionally been decided either by a centre-right alliance between the EPP, Renew and the ECR, or by a centre-left alliance between the S&D, Renew, the Greens and the Left. Since the 2019 elections, only the latter has been able to repeatedly form parliamentary majorities. During this legislature, it has been responsible for several important decisions, particularly on environmental, social and employment policies.

With both the ECR and ID expected to increase their seat share in the European elections (see Figure 1), this pattern is set to change. As the two groups remain far from a majority on their own, this will not take the form of a sweeping far-right takeover. Rather, the main beneficiary in the short run is likely to be the EPP. With the centre-left alliance projected to lose its current majority, the EPP will not only be the strongest party in the Parliament, but will also be placed in the position of a ‘pivotal’ party, without which no majority can be built (see Figure 2).

At the same time, however, the traditional centre-right alliance of EPP, ECR and Renew is not expected to win a solid majority either, and several Renew representatives have already expressed their refusal to rely on such a coalition. In order to form a right-wing majority without the S&D, the EPP would therefore have to break the cordon sanitaire with ID, which most of its member parties are not willing to do. Instead, EPP leader Manfred Weber has underlined that his group will only cooperate with parties that “meet three basic criteria. They must be pro-European. They must be pro-Ukraine. And they must be pro-rule of law”. According to Weber, this explicitly excludes the French National Rally, the German AfD (both ID), and the Polish PiS (ECR).[2] EPP lead candidate Ursula von der Leyen has ruled out cooperation with the ID group, but not with the ECR, depending “on how the composition of the Parliament is, and who is in what group”.[3]

While the EPP will thus still need to work with the other centrist groups to form parliamentary majorities, the inclusion of the more moderate wing of the ECR could allow it to dispense with the more left-leaning members of the S&D and Renew in contested votes. In the best case for the EPP, this means that the most plausible landing zone for cross-party compromises in the Parliament will be very close to the EPP’s own positions.

However, the EPP has never provided a clear definition of the “pro-European, pro-Ukraine, and pro-rule of law” criteria, nor a positive list of the parties that it considers to meet them. In fact, at the national level, its member parties are already cooperating with parties such as the Sweden Democrats (ECR), who openly threaten to take their country out of the EU.[4] In the European Parliament, too, the ECR group is unlikely to allow itself to be split by another party, but will rather use any opening to push its own policy positions. Even some ID members, such as the Dutch Party for Freedom (PVV) or the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ), could rhetorically adapt to the EPP’s criteria without necessarily abandoning their underlying political views. This lack of clarity about the line between ‘acceptable’ and ‘unacceptable’ far-right parties is likely to characterise the next parliamentary term and runs the risk of a slow normalisation of more and more extreme positions.

In any case, it should be noted that despite the rise of far-right parties, they will still be a minority in the European Parliament and can be outvoted by the centrist, pro-European groups. The extent to which the far right will be involved in building parliamentary majorities will therefore be a political decision for the other parties. A formalised coalition agreement between the centrist groups – as recently proposed by several members of the S&D, Renew, and the Greens[5] – could also lead to a more stable version of the ‘von der Leyen majority’, but it is unclear whether the EPP will be ready for this.

European Commission: Staying the centrist course

Among the EU institutions, the European Commission will be the least affected by the far-right surge. According to the EU treaties, the appointment of the Commission requires a majority in both the Council and the European Parliament. For the Commission presidency, all major European parties have once again nominated lead candidates, with incumbent President Ursula von der Leyen and Employment Commissioner Nicolas Schmit standing for the EPP and S&D, respectively. While there is no guarantee that one of the lead candidates will become Commission President, they clearly have the best chance of success. Moreover, any plausible alternative would have to be a similarly centrist figure able to win the support of both the European Council and the Parliament.

The other commissioners are proposed by the member state governments, which means that they usually belong to a ruling party in their respective country. However, the distribution of portfolios within the Commission is decided by the Commission President. This gives national governments an incentive to send commissioners who are acceptable to the President, and even member states with far-right parties in government tend to propose more moderate personalities.

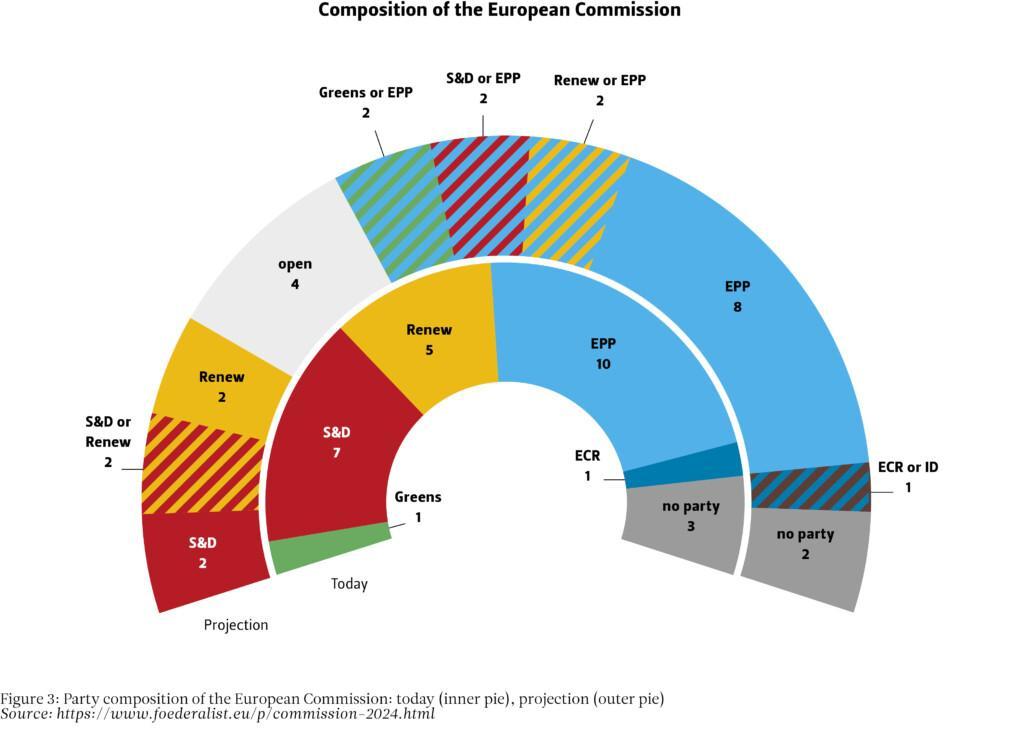

In the Commission to be elected in 2024, the number of EPP commissioners is expected to increase and could rise to more than half of the College (see Figure 3).[6] This increase will be mainly at the expense of the Social Democrats and Liberals. The far right, for its part, is likely to maintain its current low number of commissioners. Only Italy and Hungary are relatively certain to send a representative from a far-right party. As a result, the Commission can be expected to maintain its traditional centrist orientation in the new legislature, with only a moderate shift to the right as a result of the increased presence of the EPP.

Council: No ‘cordon sanitaire’ against the far right

The Council consists of national ministers representing the governments of the EU member states, in different formations depending on the policy area concerned. In countries with coalition governments, the ministers’ negotiating and voting line in the Council is usually agreed between the coalition parties; in some cases, national parliaments are also involved. Voting in the Council is therefore not primarily along transnational party lines, but is characterised by national interests. However, as national interests are interpreted from different party-political perspectives, the party composition of member state governments – and thus of the Council – also has an impact on EU policy.

In recent years, the number of member states where far-right parties participate in government has been increasing. Today, ECR member parties lead the governments of Italy and the Czech Republic, hold ministerial positions in Finland, and have a confidence-and-supply agreement that also includes cooperation on EU matters with a minority government in Sweden. The ID Party has ministers in Italy and Slovakia and is in coalition talks with other political forces in the Netherlands and Croatia. The unaffiliated far-right Fidesz controls the government in Hungary. In addition, ID member parties are leading the polls for the 2024 national elections in Belgium and Austria, and for the 2027 elections in France.

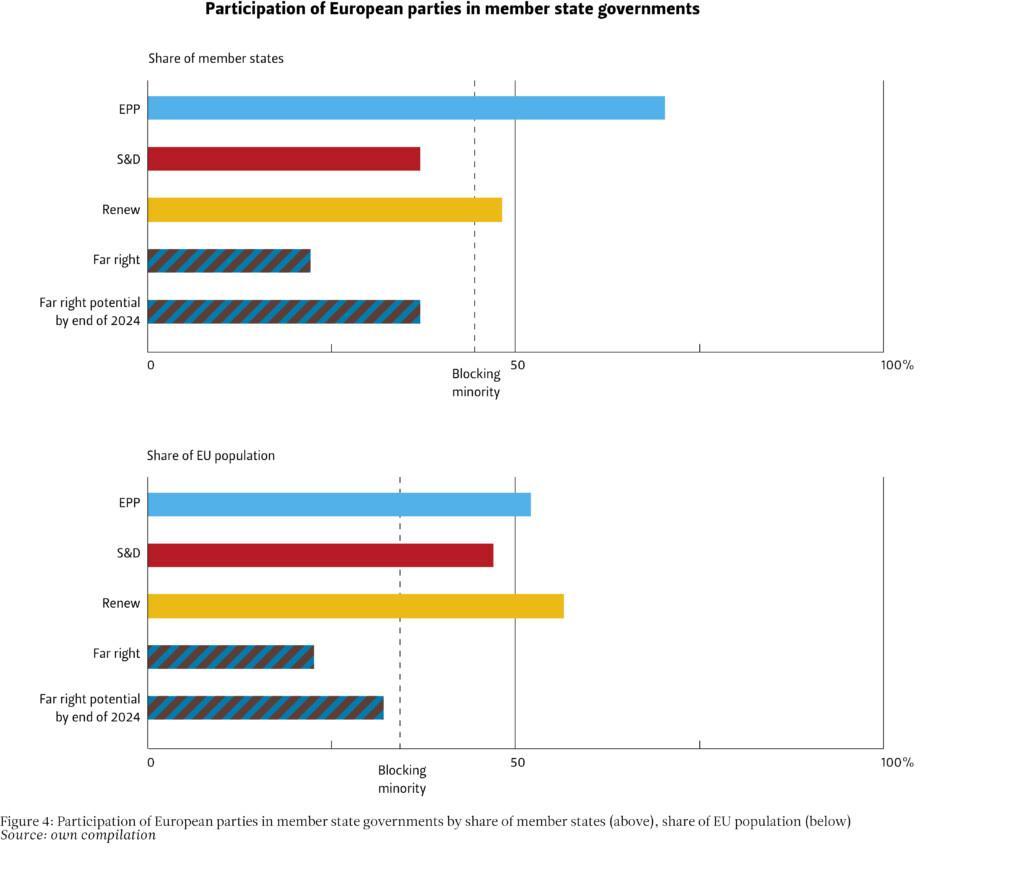

However, these governments represent only a minority in the Council. Excluding France, they represent 37% of member states and 32% of the EU’s population, which would not be enough to form a blocking minority in decisions where qualified majority voting applies (see Figure 4).[7] The far right is thus significantly weaker than the EPP, the Social Democrats, or the Liberals, each of which currently participates in governments representing at least 47% of the population. Unlike in the European Parliament, however, it is not common for representatives of centrist parties to simply outvote the far right in the Council.

There are various reasons for this: Several key policy areas – such as foreign and security policy or the EU budget – are subject to unanimity rules, giving each member state government a veto that is sometimes used to force concessions on other issues as well. Even where no formal vetoes apply, the Council is characterised by a diplomatic culture of consensus that generally seeks the broadest possible majorities, even if they are not strictly necessary for a particular decision. The fact that many far-right ministers are part of national coalition governments that also include EPP members further reduces the willingness of other member states to isolate them. Finally, there is a common concern among member states that a confrontation in the Council would lead national voters to rally around their government – as was the case with the ‘sanctions’ against Austria in 2000. As a result, there has not been a cordon sanitaire against any far-right government in the Council since then. Even in the case of Hungary’s Fidesz government, its increasing isolation over the rule of law and support for Ukraine has not been systematically extended to other policy areas.

Overall, the Council is consequently the institution that allows the far right the greatest influence on EU policy. Given its generally consensual functioning, this does not mean that far-right parties dominate Council policymaking. However, their involvement in consensus procedures allows them to participate in negotiations, set conditions for agreements, and push specific aspects of their political agenda. In past legislatures, the Council has often been to the right of the European Parliament on both constitutional and policy issues, such as migration, climate protection, or fiscal solidarity. As more far-right parties enter governments in member states, this inter-institutional divide is likely to continue.

Policy impact: Gradual normalisation of far-right positions

As the largest – and pivotal – party in the European Parliament and Commission, and a key player in the Council, the EPP, rather than the far right, is likely to have the greatest influence on the EU’s policy agenda in the coming years. Nevertheless, the projected success of the ECR and ID in the June elections will translate into more speaking time and financial resources in the European Parliament, giving their ideas more visibility in the political discourse.

At the same time, there are also signs of convergence between the centre-right and the far right in many member states. On the one hand, far-right parties with governmental ambitions have tended to moderate their rhetoric in order to appeal to a centre-right electorate and to appear acceptable to the EPP as a coalition partner. On the other hand, centre-right (and even centre-left) parties have been tempted to adopt far-right policy positions in order to win back voters lost to these parties.[8]

At the EU level, this is reinforced by the specific effect that governing parties are usually interested in presenting Council compromises to the public as their own successes. If compromises are only possible by including far-right positions, centrist parties therefore have an incentive to justify these positions as politically acceptable. In recent years, this has been evident in asylum policy, where far-right governing parties in Italy, Poland and Hungary have played a key role in shifting the debate away from the reallocation of refugees within the EU towards stricter border procedures and the externalisation of asylum applications to third countries – proposals that have subsequently also been taken up by centrist parties.

Areas that could see a similar shift to the right in the coming years include climate as well as employment and social policy, where the centre-left majority in the European Parliament has been most relevant in the 2019–24 term. On agricultural policy in particular, far-right parties have put strong pressure on the EPP to scale back its environmental ambitions. Moreover, the increased presence of ECR and ID member parties in national governments is likely to impact the upcoming negotiations on the multiannual financial framework, as well as on EU enlargement and institutional reform. Here, too, there has been a gradual convergence between the far right and the EPP, which over time has moved away from its traditional supranationalism towards more intergovernmentalist positions. In terms of EU foreign and security policy, the ID party and Hungary’s Fidesz will continue to pose a particular challenge to support for Ukraine, especially if pro-Russian far-right parties come to power in more EU member states.

Conclusions

The EU’s political system includes a large number of checks and balances and consensus mechanisms that prevent any one political actor from unilaterally imposing policy changes. As a consequence, it is unlikely that any political party in the EU will ever seize full power. At the same time, however, this consensualism also means that once far-right parties cross a certain threshold, it is very difficult for other parties to prevent them from exercising some power at the EU level.

Current seat projections do not expect the ECR and ID to be in a position where no majority can be formed without them in the European Parliament after the 2024 elections. If public attention is overly focused on the possibility of an outright victory by the far right, this could lead to a certain complacency if the ‘grand coalition’ eventually retains its majority and fears that the centre ‘might not hold’ are disproved. But such complacency would be a misreading of how parties gain power in the EU’s political system. Indeed, even a partial rise of the far right will be very difficult for centrist parties to ignore. The EPP, in particular, will be tempted to make the most of its new pivotal role in the Parliament by shifting the line on who constitutes an acceptable cooperation partner. Even more consequential is the presence of the far right in an increasing number of national governments and, as a result, in the Council.

A realistic scenario for how the far right will gain influence over EU policy is therefore not through a sweeping victory but rather through creeping normalisation: not an overwhelming success in the EU elections, but a gradual involvement in decision-making. In this context, the very mechanisms that are supposed to best protect national sovereignty (such as unanimity procedures in the Council) are paradoxically the ones most likely to give far-right parties a foothold in EU politics – even at a time when they represent only a minority of EU citizens and could still be outvoted in a more majoritarian democracy.

Endnotes

[1] Müller, Manuel (2024) “European Parliament seat projection (April 2024): EPP far ahead, third place remains contested, Greens regain ground”. Der (europäische) Föderalist, 26 April 2024. https://www.foederalist.eu/2024/04/ep-seat-projection-april-2024.html.

[2] Georgian, Armen (2023) “We won’t work with far-right ‘extremists’, EPP chief Manfred Weber says”. France 24, 26 May 2023. https://www.france24.com/en/tv-shows/talking-europe/20230526-we-won-t-work-with-far-right-extremists-epp-chief-manfred-weber-says.

[3] Wax, Eddy (2024) “Von der Leyen opens the door to Europe’s hard right”. Politico, 30 April 2024. https://www.politico.eu/article/von-der-leyen-hard-right-maastricht-debate-giorgia-meloni-viktor-orban-schmit/.

[4] Åkesson, Jimmie and Charlie Weimers (2024) “Sverige först” ska gälla i EU-politiken. Aftonbladet, 13 February 2024. https://www.aftonbladet.se/debatt/a/15Kp3X/akesson-sverige-forst-ska-gallai-eu-politiken.

[5] Cf. Griera, Max (2024) “Pro-EU parties consider written commitments to tackle political mistrust”. Euractiv, 04 April 2024. https://www.euractiv.com/section/elections/news/pro-eu-parties-eyeing-written-commitments-to-kill-mistrust/.

[6] Müller, Manuel (2024) “The 2024 Commission”. Der (europäische) Föderalist, 10 April 2024. https://www.foederalist.eu/p/commission-2024.html.

[7] Under qualified majority voting, governments representing 55% of the member states and 65% of the population are required for a decision. This means that the blocking minority is 45% of the member states or 35% of the population.

[8] This is despite empirical evidence indicating that such a strategy does not pay off for centrist parties. Cf. Krause, Werner, Denis Cohen and Tarik Abou-Chadi (2023) “Does accommodation work? Mainstream party strategies and the success of radical right parties”. Political Science Research and Methods. 11(1): 172–179, doi:10.1017/psrm.2022.8.