Sen jälkeen kun Volodymyr Zelenskyi valittiin Ukrainan presidentiksi vuonna 2019, tämän Venäjä-politiikkaa on määrittänyt vaalilupaus rauhan tuomisesta Ukrainaan. Sopimuksen saavuttaminen presidentti Vladimir Putinin kanssa henkilökohtaisesti oli Zelenskyille erityisen tärkeää.

Zelenskyin Venäjä-politiikkaa auttavat ymmärtämään hänen henkilökohtainen ja liiketoimiin kytkeytyvä menneisyytensä, poliittisen kokemuksen puute sekä ongelmat Ukrainan ja lännen välisissä suhteissa.

Zelenskyin suhtautuminen Venäjään oli ulkopoliittisesti epärealistinen, sillä Venäjä odotti tämän pikemminkin antautuvan kuin pyrkivän neuvottelemaan sovintoa. Zelenskyin Venäjä-politiikka jakoi mielipiteitä myös sisäisesti, sillä monet ukrainalaiset eivät pitäneet hyväksyttävänä rauhansopimusta, jonka hintana olisi ollut myönnytykset periaatekysymyksissä.

Pyrkimys ymmärrykseen Moskovan kanssa heikensi vähitellen Zelenskyin poliittista asemaa Ukrainassa. Vastauksena hänen oli tiukennettava kantaansa Venäjään ja venäjämielisiin toimijoihin, mutta suunnanmuutos oli vain osittainen.

Venäjän aloittama hyökkäyssota on muuttanut perusteellisesti Ukrainan yhteiskuntaa ja politiikkaa. Presidentin linja on muodostunut erottamattomaksi osaksi uutta kansallista sota-ajan konsensusta suhteessa Venäjään.

Introduction

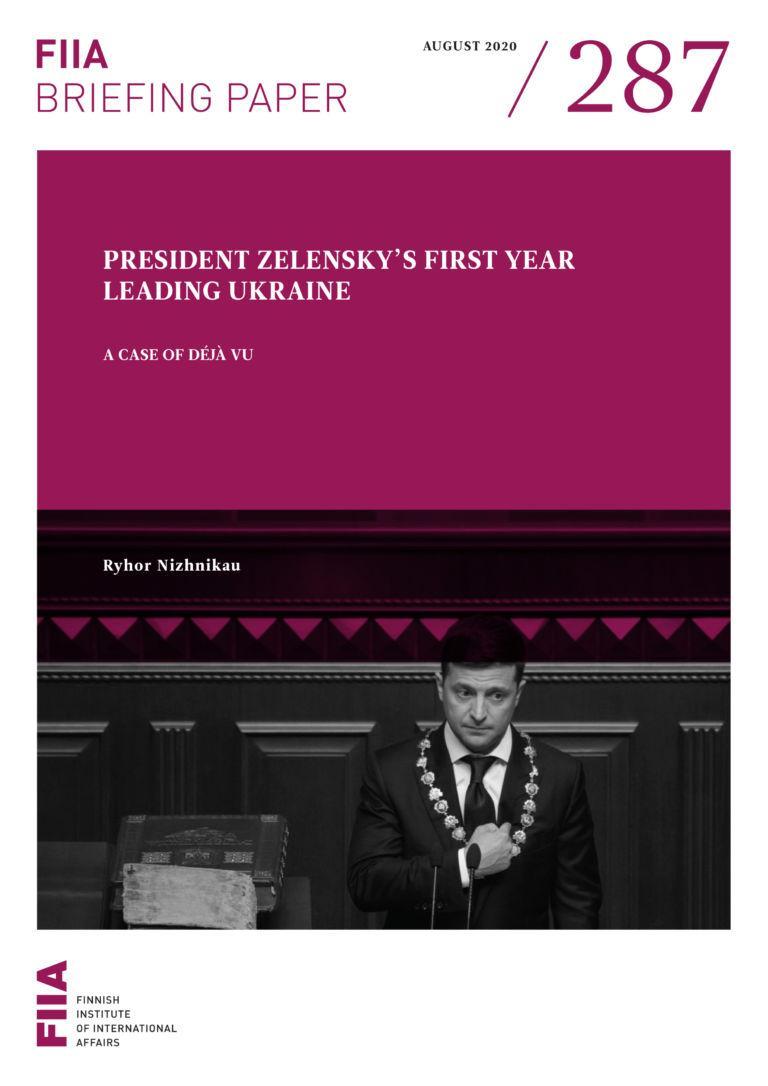

After 24 February 2022, Volodymyr Zelenskyy turned into a globally lauded figure. His leadership during the Russian invasion has made him the face of Ukraine’s heroic resistance, and has won him recognition and admiration around the world.

This would not have been possible without Zelenskyy’s endorsement as national leader by the Ukrainian people. It no longer matters that, before the invasion, Zelenskyy’s domestic record was mixed at best. His team was heavily criticized for incompetence, nepotism and corruption, Ukraine’s relations with the West were faltering, the government’s Russia policy had produced few results, and only 18.6% of Ukrainians wanted Zelenskyy to run for re-election.[1]

Although the war’s overall effect on Ukrainian politics and society is impossible to determine as the war continues, this Briefing Paper attempts to assess its impact on Zelenskyy’s approach towards Russia, which is, on the contrary, rather evident despite being a moving target as well. The paper will trace the trajectory of Zelenskyy’s Russia policy from his presidential campaign of 2019 to the present day. It is argued that the evolution of Zelenskyy’s Russia course largely followed public demand, which was limiting his space for would-be concessions. Nevertheless, it is conceivable that if Moscow had demonstrated the will for a compromise in 2019–2021, Zelenskyy would have reciprocated, despite internal opposition.

2019: Seeking a blitz-peace

Zelenskyy’s political rise largely stemmed from a demand for a peaceful settlement of the conflict in Eastern Ukraine, which he pledged to deliver. As a presidential candidate, he expressed his readiness to “do everything” to stop the war. A sustainable ceasefire in Donbas was the central element of his electoral programme, and designated a top priority in his inauguration speech.

The new administration distinguished itself from that of its predecessor Petro Poroshenko in three key aspects, duly demonstrating a certain readiness to accommodate Russia’s interests. First and most strikingly, the new Ukrainian authorities chose to refrain from public criticism of Russia with regard to the conflict. The thesis “Russia is an aggressor” disappeared from the official discourse. In addition, Kyiv deliberately avoided making public comments on such contentious issues as the then ongoing international arbitration of several bilateral economic disputes, or Germany’s decision to construct the Nord Stream 2 pipeline.

Second, Zelenskyy – perhaps inadvertently – re-broadcast some of Russia’s narratives on the war. He partially accepted Russia’s view on the conflict as “Ukraine’s domestic problem”, and admitted the loss of the minds and hearts of people in the breakaway territories. He linked the resolution of the conflict to “winning them back”[2] and making them “realize that they are Ukrainians”. [3]

Furthermore, Zelenskyy put the blame for the continuation of the conflict in Donbas on the Ukrainian elites. He accused the previous administration of unwillingness to stop the war and criticized Ukraine’s politicians and media for various delays and setbacks.[4] Zelenskyy specifically wanted to prosecute Petro Poroshenko for his decisions related to military operations in the eastern part of the country.

Third, at the practical level, Ukraine re-endorsed the Minsk process, two sets of peace agreements signed in September 2014 and February 2015 respectively, as the main instrument for conflict settlement, although Zelenskyy had branded it “useless” during his campaign. During his third week in office, on 3 June 2019, Zelenskyy urged the unblocking of the Minsk process unconditionally. The following day, he announced Ukraine’s readiness to implement the Minsk agreements and hold peace talks with Russia. Later, he committed to complying with any terms that would be approved in a popular referendum. In September 2019, Ukraine yielded to Russia’s demand to include Vladimir Tsemakh, a war crime suspect wanted by Dutch prosecutors, and a key witness in the MH17 investigation, in the exchange of prisoners of war. This was largely viewed in Ukraine as a huge and unwarranted concession.

In December 2019, on the eve of the Paris summit of the so-called Normandy Four (France, Germany, Russia, Ukraine), presumably in order to guarantee Putin’s personal attendance, Ukraine took one more step back from what had been considered its position of principle. Despite Kyiv’s previous promises not to hold elections in the separatist areas until foreign troops were withdrawn, Ukraine’s then minister of foreign affairs, Vadim Pristayko, publicly accepted the so-called Steinmeier formula, named after Germany’s former foreign minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier, so that the sequence of events could be changed and the elections could precede the troop withdrawal.

The roots of misunderstanding about Russia

Zelenskyy’s strategy derived from several sources. Apparently, as populist politicians often do – and Zelenskyy was undoubtedly a populist when coming to power – he believed in simple solutions to complex problems. This is illustrated in his statements, such as “in my mind the war has already ended”, or that in order to stop the war “[we] simply need to stop shooting [ourselves]”.[5]

Zelenskyy’s understanding of Russia and Putin naturally originated from his background. As a Russian speaker from Eastern Ukraine, who was alien to ethno-nationalism, had largely made his acting career in Moscow, and had been doing business in Russia and working for Russia-oriented Ukrainian tycoons, Zelenskyy must have had sympathies for and illusions about contemporary Russia and its ruling circles. His political premises, as convincingly evidenced in his domestic politics, were eclectic and included a preference for informal mechanisms over institutions, acceptance of paternalistic methods of governance, and striving towards ruling with a “strong hand”. This may partially explain Zelenskyy’s perception of a personal meeting with Putin as the shortest route to resolving all conflicts, and his apparent opinion that it is not Putin but his entourage that is resisting the resolution of the conflict on the Russian side.

Zelenskyy’s own inner circle echoed and reinforced his attitudes and beliefs. Andriy Yermak, the main negotiator with Russia, who in early 2020 became the head of the presidential administration, had been boasting about close ties with Russian elites and apparently persuaded Zelenskyy with regard to “selling” his ability to deal with Moscow informally. Serhiy Sivoha, an advisor to the National Security and Defence Council, and Serhiy Shefir, assistant to the president, were products of the Soviet epoch, and were generally favourably disposed towards Russia. Several members of the pro-presidential Servant of the People party’s faction in parliament, such as Maksim Buzhanski, actively spread pro-Russian and pro-Soviet narratives. The presidential team even included members who were openly suspected of being agents of Russian influence, such as the former official of President Viktor Yanukovych’s administration, Ruslan Demchenko, and the deputy head of the Main Investigation Department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs during Yanukovych’s presidency, Oleh Tatarov. Quite plausibly, some of them might have argued that Putin is a “smart person” with whom one can make deals.[6]

In turn, Moscow initially also fostered Zelenskyy’s willingness to make a deal. After the July 2019 parliamentary election, which cemented Zelenskyy’s position of power, Russia indicated some readiness to promote the peace process. It endorsed the informal tracks at the level of presidential administrations as the main mechanism for negotiations. In October of the same year, it unblocked the process of separation of forces in two sections of the military line of contact. The humanitarian dialogue led to two exchanges of prisoners of war (in September and December 2019) and the construction of a bridge in Stanitsa Luhanska to facilitate the movement of people. Worth a separate mention, a gas transit contract between Ukraine and Russia was extended until 2024.

Meanwhile, relations between Zelenskyy and the West were plagued by mistrust and misunderstandings. From the beginning of his presidential term, Zelenskyy featured in US domestic political scandals. Kyiv faced pressure from Donald Trump’s administration, seeking to obtain damaging information on presidential candidate Joe Biden’s son, Hunter Biden. When Joe Biden was elected as the new US president, against some expectations, he did not treat Ukraine as a priority either. Zelenskyy’s visit to Washington was postponed several times. International financial institutions were increasing conditionality when negotiating economic assistance for Kyiv. Unlike Poroshenko, Zelenskyy had a hard time building functioning relations with the German and French leadership. All of this merely served to add to Zelenskyy’s grievances regarding the insufficient Western support for Ukraine and its alleged hypocrisy. The rhetoric about Ukraine as a strong independent state, a subject and not an object of international relations, was partially built on this disappointment.

2020: Farewell to illusions

The Normandy Four summit held on 9 December 2019 did not live up to Zelenskyy’s expectations.[7] The failure, however, did not immediately affect the Ukrainian policy. A few days later, on 13 December, Zelensky brought a draft law to parliament on the decentralization of power in the country, which included a clause on the special status of the breakaway territories in Donbas.[8] In March 2020, Yermak reportedly signed a protocol by the Trilateral Contact Group (Ukraine, Russia, OSCE), which established a so-called Advisory Council consisting of representatives of Ukraine and those of the separatist entities, which indicated their implicit recognition by Ukraine and – again – was at odds with the fundamentals of Kyiv’s political position. In May 2020, Zelenskyy reiterated his promise to end the war in Donbas, stating that this would happen during his term in office.[9] In July 2020, a complete and comprehensive ceasefire regime was announced in Donbas, which Zelenskyy insisted was working despite constant violations, documented by the OSCE monitoring mission.

Yet, in the autumn of 2020, Ukraine’s official position evolved. Primarily, this was a result of the realization that Moscow had no intention of resolving the conflict. At the rhetorical level, Ukraine openly and unequivocally blamed Moscow for undermining the conflict resolution. At the formal diplomatic level, Ukraine officially rejected the above-mentioned Steinmeier formula. Instead, Ukraine insisted on the unconditional withdrawal of Russian forces. In October, Zelenskyy promised that the temporarily occupied territories of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions would not receive an autonomous status.

Several factors seem to have made Zelenskyy amend his stance. To begin with, the Ukrainian side could no longer deny that agreements with Russia were not being honoured. The inability to organize the second Normandy Four meeting is a classic example. None of the clauses agreed upon in the joint communiqué at the Paris Summit, except for the exchange of prisoners at the end of 2019, were realized. Measures to stabilize the situation in the conflict zone were not implemented. The ceasefire was consistently violated, and further prisoner exchanges were halted while Zelenskyy’s projects for the separation of troops in Donbas were simply ignored.

More importantly, Zelenskyy gradually reached the limits of manoeuvre in Ukraine’s domestic politics. His decisions such as the endorsement of the Steinmeier formula or the allegedly promised restoration of the water supply to Crimea, which had been cut after the peninsula’s annexation by Russia in 2014, immediately triggered public outrage and protests. The electoral defeat of the Servant of the People party in local elections in October 2020 was a critical wake-up call. The elections showed that the ruling party was losing ground both to pro-Russian forces in the east and to pro-Western forces in the west of the country. Such a turnaround persuaded the president to take public opinion seriously.

Meanwhile, Russia’s attitude to Zelenskyy also took a turn for the worse. Zelenskyy’s inability to “compromise” and his growing political vulnerability created a situation in which Moscow began to explicitly treat him no differently from Poroshenko. Contacts between administrations were frozen. Russia suspended the negotiation track at the level of foreign ministries and in practice boycotted the Normandy Four format. Putin discussed the Donbas peace settlement with Western leaders but not with Zelenskyy. Whereas in 2019 five phone conversations took place between Zelenskyy and Putin, in 2020 only one was arranged.

2021: Still vacillating

At the beginning of 2021, the situation in the conflict zone began to incrementally worsen. Ukraine was regularly sustaining casualties. The concentration of Russian troops along the Ukrainian border in spring threatened an expansion and escalation of the conflict. Political pressure was increasing as well, manifested in the activation of pro-Russian political forces within Ukraine and the intensification of the integration process of the breakaway territories with Russia, not least by the wholesale granting of Russian citizenship to the local population. The approaching completion of the construction of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline and the imminent cut-off of the gas transit was the focal point of Russian economic pressure.

The Ukrainian authorities, in turn, looked rather disoriented. Ukraine mainly continued to invest in diplomacy, focusing on new plans for conflict resolution. Throughout most of the year, Ukrainian representatives were pushing for the revision of the Minsk agreements and the reanimation of the Normandy format, but Kyiv’s steps remained contradictory. A discussion concerning a new venue for the Minsk group meetings, and proposals to involve Washington and London in the procrastinated talks were periodically interrupted by Zelenskyy’s return to his almost obsessive idea of meeting Putin one on one.

Zelenskyy’s concerns regarding the West also increased. His frustration with the West and mistrust of Western politicians over what he saw as the appeasement of Putin and insufficient support for Ukraine intensified. As contacts between the Biden administration and Russia grew, culminating in the US-Russia summit in Geneva in June, Washington was indeed sending disturbing signals to Ukraine. On the one hand, the White House refused to deliver the armaments that Ukraine had requested and agreed not to block Nord Stream 2 in order to cement the allied relationship with Germany. On the other hand, the US administration criticized Kyiv for the lack of political and economic reforms, which was justified in principle but misleading in the current context. Fears of a backroom deal over Ukraine only re-fuelled Zelenskyy’s reproachful rhetoric against the West.

The expansion of Ukraine’s diplomatic efforts regarding Crimea was, however, a qualitative change. The establishment of the Crimean Platform, a diplomatic initiative to restore Ukraine’s sovereignty over Crimea, was a substantial foreign policy success for Kyiv. The inaugural summit, held in Kyiv in August 2021, hosted 47 countries and international entities, including the EU and NATO. Most importantly, it signalled Ukraine’s readiness to internationalize the Crimean agenda, including the internal situation on the annexed peninsula, despite Moscow’s view on the issue as closed and non-negotiable.

Domestic challenges were nevertheless mounting. Zelenskyy’s approval rating in February 2022 fell to 24%, compared with 73% in September 2019.[10] The president found himself under constant political and media attacks. The inconsistency of his Russia policy was emphasized in different parts of Ukraine’s political spectrum. The pro-European opposition insisted on the need to draw clear red lines and put more pressure on Moscow, whereas the pro-Russian opposition accused Zelenskyy of stalling the peace process. The inability to pass several key presidential draft laws along with the launch of a new political project by the former speaker of parliament and a key figure in Zelenskyy’s 2019 campaign, Dmytro Razumkov, indicated deep splits within their own ranks. The so-called “Wagnergate” investigation[11] raised questions about the presidential administration’s very allegiance to national interests.

In this situation, Zelenskyy’s attention was naturally drawn to domestic affairs and the struggle with his political opponents. In February 2021, the Ukrainian authorities moved against one of the leaders of the main pro-Russian “Opposition Platform – For Life” party, Viktor Medvedchuk, who was personally related to Putin (the latter being the godfather of Medvedchuk’s daughter). The National Security and Defence Council’s decisions to shut down three TV channels owned by Medvedchuk and to freeze his assets immediately boosted Zelenskyy’s popularity. In May, charged with high treason, Medvedchuk was put under house arrest. In summer, Zelenskyy started a campaign against oligarchs and specifically against Rinat Akhmetov, Ukraine’s richest man. Zelenskyy publicly attacked Akhmetov for malign political and media influence, and openly accused him of being implicated in a planned coup d’état. However, at the same time, it was former President Poroshenko, the leader of pro-Western forces but also an oligarch, who was on Zelenskyy’s agenda as the main target. In January 2022, Poroshenko, like Medvedchuk, was accused of colluding with Russia and the militants of the breakaway regions during the hostilities of 2014–2015. The court froze his assets and forbade him from leaving the Kyiv region.

All of these inconsistencies and zigzags indicate that up until the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Zelenskyy was still unable or unwilling to make a definitive choice. It was Moscow which made it for him.

Looking forward: Forging a new course

In the coming months and years, the war against Russia will continue testing Ukraine’s resilience. Yet its main effect is already clear. The war has revitalized Ukrainian society. It has united the nation and eradicated some of the previous ambivalences. In mid-March 2022, a record number of Ukrainians in all age groups and regions believed that Ukraine was moving in the right direction, and trusted key institutions.[12] Ukrainians embraced a new European course and values, which were previously often perceived as declarative, and re-affirmed the choice in favour of NATO membership.

The war has completely reshaped Ukrainian thinking with regard to Russia. The destruction of Russian-speaking southern and eastern regions and the murder of Russian speakers abruptly overturned public attitudes. In March 2022, 56% of Ukrainians believed that the Russian goal was the total annihilation of the Ukrainian people, and 49% thought that it was the occupation and incorporation of Ukraine into Russia. Consequently, the nation increasingly speaks against any concessions to Moscow. Seventy-five per cent of Ukrainians would reject a deal over Crimea even if it ended the war.[13] Pro-Russian parties, which can no longer have a political future in their old form, exclude members that continue to spread pro-Russian narratives.

The tragic reality erased Zelenskyy’s 2019 agenda and permitted his government to start with a clean slate. Zelenskyy, equally unexpectedly for many in Ukraine, Russia and the West, rose to the challenge and took on the role of national leader. His narrative on Russia and the war has struck a chord with the public, and has received widespread acclaim in Ukraine. In this regard, although it is too early to accurately predict the scope and depth of the changes in Ukraine’s politics and society until it is known how the war ends, Zelenskyy’s transformation corresponds to the far-reaching societal shifts.

That said, the danger of national consolidation starting to erode and of old political ills reappearing can be sensed. The rifts among the political establishment have not been completely eliminated and should not be overlooked. The West has a role to play in maintaining Ukraine’s unity and in anchoring its future as a democracy and a prosperous economy. To this end, the West should redouble its efforts to help Ukraine in this war, and offer Ukrainians a clear vision of a European future. An unequivocal and realistic prospect of EU membership, coupled with a plan for the country’s post-war reconstruction, would be the first step in the right direction.

Endnotes

[1] ‘Suspilʹno-politychni nastroyi naselennya ukrayiny: vybory prezydenta ukrayiny ta verkhovnoyi rady ukrayiny za rezulʹtatamy telefonnoho opytuvannya, 20–21 sichnya 2022 roku’, KMIS, 21 January 2022, https://www.kiis.com.ua/?lang=ukr&cat=reports&id=1090&page=1.

[2] ‘Peredvyborna kampaniya Zelensʹkoho: Krym, Donbas i vyaznytsya za nesplatu podatkiv’, 1 April 2019, Fakty, https://fakty.com.ua/ua/ukraine/20190401-peredvyborna-kampaniya-zelenskogo-krym-donbas-i-vyaznytsya-za-nesplatu-podatkiv/.

[3] ‘Inavhuratsiyna promova Prezydenta Ukrayiny Volodymyra Zelensʹkoho’, 20 May 2019, President.gov.ua, https://www.president.gov.ua/news/inavguracijna-promova-prezidenta-ukrayini-volodimira-zelensk-55489.

[4] ‘Viyna ta myr v obitsyankakh Zelensʹkoho: yak zminyuvalasya rytoryka prezydenta shchodo Donbasu’, 27 July 2021, Slovo i Dilo, https://www.slovoidilo.ua/2021/07/27/stattja/polityka/vijna-ta-myr-obicyankax-zelenskoho-yak-zminyuvalasya-rytoryka-prezydenta-shhodo-donbasu.

[5] S. Gorbatenko. ‘Zelenskiy i voyna na Donbasse: chto izmenilos' za dva goda’, 20 May 2021, Radio Svoboda, https://www.radiosvoboda.org/a/vladimir-zelenskiy-donbass/31263220.html.

[6] N. Dan’kova. ‘Sovladelets studii “Kvartal 95” Boris Shefir: “Kvoty i zaprety – eto plokho”’, 30 May 2019, Detector Media, https://detector.media/rinok/article/167733/2019-05-30-sovladelets-studyy-kvartal-95-borys-shefyr-kvoty-y-zaprety-jeto-plokho/.

[7] A. Moshes. ‘The Normandy Summit on Ukraine: no winners, no losers, to be continued’. FIIA Comment 14, 2019, https://fiia.fi/en/publication/the-normandy-summit-on-ukraine.

[8] ‘Movchannya dlya Putina: chomu stratehiya Zelensʹkoho vede do prohrashu Ukrayiny’, 11 November 2019, Evropeyska Pravda, https://www.eurointegration.com.ua/rus/articles/2019/11/11/7102904/.

[9] ‘Zelenskiy uveren, chto za svoyu kadentsiyu zakonchit voynu na Donbasse’, 22 April 2020, Ukrainska Pravda, https://www.pravda.com.ua/rus/news/2020/04/22/7248937/.

[10] Rating Group, ‘Zahalʹnonatsionalʹne opytuvannya: Ukrayina v umovakh viyny (26–27 lyutoho 2022)’, 27 February 2022, https://ratinggroup.ua/research/ukraine/obschenacionalnyy_opros_ukraina_v_usloviyah_voyny_26-27_fevralya_2022_goda.html.

[11] The “Wagnergate” investigation looks into a derailed July 2020 operation to capture Russian mercenaries, many of whom fought in Donbas. During 2021, reports increasingly implicated the president and his administration in the failure of the operation.

[12] Rating Group, ‘Chetverte Zahalʹnonatsionalʹne Opytuvannya Ukrayintsiv v Umovakh Viyny’, 12–13 March 2022, https://ratinggroup.ua/research/ukraine/chetvertyy_obschenacionalnyy_opros_ukraincev_v_usloviyah_voyny_12-13_marta_2022_goda.html.

[13] R. Halilov. ‘Ukraincy ne gotovy otdat’ Rossii Krym’, March 11, 2022, https://ru.krymr.com/a/ukraintsy-ne-gotovy-otdat-rossii-krym/31747675.html.